Typographic Conventions

-

Italic script where the focus is on specific lexical items, for example: woe

Small capitals for lexis which represent headwords and their inflections, such as KNOW [knew, knowledge]

Small capitals for speech act functions, for example: WARNING

Bold typeface used for emphasis

Original spellings and punctuation are retained in the extracts from the writings.

Introduction

There is a wealth of primary and secondary evidence relating to the existence of Quaker publishing in the seventeenth century. We know that there was an explosion in the production of tracts, books, pamphlets and broadsides dating from the 1650s onwards. We know how Friends embarked on this campaign using the technology of the time: cheaper paper, availability of printing presses and professional printers. This is an area of modern scholarship in itself (see O’Malley 1982; Smith 1989; Holstun 1992; Green 2000; Peters 2005; Hagglund 2013). Before the imposition of censorship in the 1660s anyone in the Quaker movement who could get a manuscript printed was free to disseminate open letters, tract texts and much else. This material was used for public preaching, often open-air happenings wherever an audience could be persuaded to listen. Copies were also transported around the country and overseas by a growing network of Friends on horseback or on foot—this activity was confined to George Fox initially, but very soon it involved a large group of dedicated travelling Friends. Primary sources about these journeys include meta-information in handwritten letters and published material. From the inception of the Second Day Morning Meeting in 1673 we have evidence from the minutes of which texts were submitted and accepted or rejected. We also know why these first generations of Quakers were so energetic in this regard. I will return shortly to the question of why Friends were so impelled to embrace a campaign using modern (for the time) print culture, but what has received little attention so far are the rhetorical strategies they employed in their efforts to exhort and convince. These people made use of a wide variety of persuasive techniques, linguistically speaking. Such devices were known from Aristotle’s time onwards and used to great effect, and indeed are familiar to us today through the domains of advertising and marketing, political activity, and just about anyone with a website or a personal blog. Persuasion is everywhere, sometimes employed more effective than at other times. Quaker Studies readers may feel uncomfortable with the implied link to ‘selling’, but my argument is based on a morally neutral stance, looking rather to exploring concepts of communicative persuasion in all its forms.

This paper presents an analysis of Quaker rhetorical strategies that were aimed at convincing as many of the general public as possible of the rightness of the new faith and practice that early Friends had discovered. Some authors were educated and clearly reached for classical Ciceronian-style methods. William Penn, Isaac Penington and Robert Barclay come to mind, for instance. Others, tradesmen and women with some education, or labourers and those in service, relied on native invention, or what they had learnt elsewhere, to get their urgent message out ‘from the Lord’. The question in my mind which I am so far unable to resolve is: how effective in the long term was that campaign of persuasion? I return to this in my conclusion.

The paper falls into two parts. The first analyses a broad range of seventeenth-century publications from a surface-level lexical perspective. I present some typically persuasive devices: repetition, directive speech acts of warning and exhorting, and apocalyptic fear-appeal language. All these come under the rhetorical umbrella of emotion (classical pathos). The second part goes deeper by means of analysis at the discourse level of just one text, Stephen Crisp’s A Plain Path-way Opened to the Simple-hearted (1668). I discovered in this a rather more mature and reflective strategy for promoting the Quaker message of the time. The style here is mostly pathos, but includes a glimpse of logos—a reason-based stance.

So, what was the message that early Friends were so single-mindedly intent on conveying? Who were the targets of this initiative? ‘All the Inhabitants of the Earth’ were addressed by George Watkinson (1661). Less ambitiously there was ‘Woe to thee, town of Cambridge’ (Esther Biddle 166-) and ‘This is for you all, the Inhabitants of Whitwell’ (Richard Bradly 1662). An example of a potential overseas readership comes in a text called A Warning to the Inhabitants of Barbados (John Rous 1665).

For extensive discussion about how early Friends set about preaching, convincing and disputing in public arenas see Bauman’s (1998) chapter 5, which includes a useful explanation of Fox’s style in particular (pp. 77–83). Other important studies describing how and why Friends were so involved in pamphleteering and public preaching include Peters, Loewenstein, Smith and Keeble in The Emergence of Quaker Writing (Corns and Loewenstein 1995). These authors focus on different aspects of Quaker activities of exhortation and convincement. Hinds (2011: 43) discusses Quaker preaching and the use of ‘sacred eloquence’. She compares Quaker methods with Debora Shuger’s (1993: 123) position on sacred rhetoric theory generally. Shuger posits two traditions—conservative and liberal—but, according to her, both use emotion and affect in their approach. The Quaker practice appears therefore not too distant from orthodox Protestant preaching, and indeed the present study makes no claim for distinctiveness in this regard. I suggest that Quaker persuasion texts of exhorting and convincing go beyond the limits of preaching to embrace discourses of disputing and personal narrative testimony. Other useful studies in this rich field include Morrissey (2002) on English theories of preaching and exhorting and Parry (2017), which touches on similar themes to the present study, but focusses on Puritan persuasion techniques using the lens of classical rhetorical strategies.

The evidence in my Quaker Historical Corpus dataset reveals two broad strands of argument in texts up to about 1675: i) warning people of an impending apocalypse—the ‘Day of the Lord’, which was thought soon to be upon everyone as the end-times arrived; and ii) a systematic campaign to promote a radical Christian ethic. Christopher Hill characterised such thinking (referring in this case to Gerrard Winstanley) as a ‘politico-ideological role of religion and law’ (Hill 1977: 276). Quaker writers promoted such demands as liberty of conscience, equality of rank, reform of the Christian church, release from compulsory payment of tithes to the Church of England and refusal to swear on the Bible an allegiance to the English monarchy. The above is not exhaustive—the shopping list goes on, as the mission of these Friends was to seek widespread utopian reform.

Theoretical Background and Approaches to the Analysis

Suasive communication across all domains and periods of history has been extensively studied. This is not the place to explore this theoretical field in detail, but a few generalisations and claims from the literature may be useful at this point. The principles of rhetoric, as understood in the nineteenth century, are explained by A. S. Hill (1896). A century later, Bender and Wellbury’s 1990 anthology goes into a wide-ranging variety of perspectives on the central concepts, bringing the historical field into the present era. The historical and philosophical aspects are covered in a linguistics study by Crespo-García (2011), but for a handbook/textbook on the field Dillard and Pfau (2002) would be a comprehensive resource, as it offers summaries of all the recent developments in the field. Philosophical and other theoretical aspects of persuasion are beyond the scope of the present study, whose focus of analysis remains linguistic and discoursal as well as specifically Quaker.

It is clearly impossible to separate Quaker thinking into either religious or political categories. For Friends, the two have always been interchangeable in a non-party-political way. The present article, therefore, makes no attempt to strip out the political aspects of persuasion from the spiritual. Robert Denton makes a statement that is a useful starting point for a consideration of political rhetoric dating back to Aristotle, which I suggest reflects the Quaker combined perspective: ‘Formal or informal, verbal or nonverbal, public or private, [political rhetoric is] always persuasive, forcing us consciously or subconsciously to interpret, to evaluate, and to act’ (Denton 1996: ix, in Halmari 2005: 107).

Quaker exhortatory rhetoric is mostly verbal but perhaps the trope of ‘going naked for a sign’ (for example, see Romack 2011) may be seen as a nonverbal expression of persuasion. Others include ‘hat honour’ (refusing to doff a hat as a marker of civil politeness) as a physical marker of witness. As we shall see later in this paper, Friends were working hard to engage others publicly in churches and marketplaces but were also disputing with each other as they sought to formalise what they understood to be their true Quaker testimony. Interpretation and criticism came especially from those strongly against the Quaker position, often in vitriolic discourse. A second quotation explains an approach replicated in the present language-based enquiry. I too look for ‘Linguistic choices that aim at affecting or changing the behaviour of others; or strengthening the existing beliefs and behaviours of those who already agree—the beliefs and behaviours of persuaders included’. (Halmari and Virtanen 2005: 5). This is a good description of the underlying purpose found in many Quaker texts. Writers were seeking to convince members of the public as well as those in the church, government or judiciary. They also wrote pamphlets based on manuscripts and open letters addressed to groups of fellow Quakers (Green 2000: 411). We shall investigate publications that employ strategies for EXHORTING and WARNING those not yet convinced by Quakerism.

In my research I use simple corpus-based tools such as word frequency lists to detect grammatical and lexical patterns distributed across a range of texts. I combine this approach with close reading of larger stretches of text or complete pamphlets. My knowledge of previous linguistic research into rhetoric (Roads 2015; 2018) initially suggests suitable lines of enquiry. In the present study, an iterative process of investigation has revealed types of expression used by many authors in their attempts to persuade their audiences. The results, of course, relate only to the texts in the corpus, but because of the breadth of authorship and the non-subjective approach using automatic retrieval of linguistic items I am reasonably confident that my findings would be replicated in a yet larger sample with a similar date range.

Findings

Simple lexical repetition is a frequent stand-by for persuasive speech-like markers employing Aristotelian pathos, used by politicians and sermonisers over the centuries. It reinforces an argument and helps to ensure that the point being made stays in the mind of the addressee(s). For one example out of a wide choice, observe the simplistic phraseology of Swinton:

-

1)

The whole, the whole, the whole earth shall not hinder it; verily, the whole earth shall not hinder it. (Swinton 1663)

Fox, in Ex. (2) slightly abridged, takes this approach even further in a way that Cope (1956: 733) has described as incantational: ‘an incredible repetition, a combining and recombining of a cluster of words and phrases drawn from Scripture’. Fox is reworking John 1:5–9 in a hypnotic weaving of the items darkness, LIGHT, COMPREHEND and SHINE.

-

2)

The light of men, and the light shined in darkness, and the darkness comprehended it not: … and this the true light that doth enlighten every man that cometh into the world, which light shineth in darkness, and darkness comprehendeth it not. Now mark, it is there. What? Doth it shine in darkness, and darkness comprehendeth it not? Is not this the state that the world knew him not, nor the Pharisees knew him not, though the Kingdom of heaven was within them, and light shined in darkness, and darkness comprehended it not. Here’s the unconverted estate; so he came to his own, and his own received him not; light shines in darkness, and darkness comprehends it not. You were darkness saith the Apostle, but now are ye light in the Lord. Walk as children of the light … Heres light shines out of darkness, God had commanded it to shine out of darkness. (Fox 1657)

Another type of repetition, which attempts to strengthen a sense of emphasis, uses the pragmatic repetition of a specific linguistic form such as a string of adjectives,1 as in this splendid example (3). There is prosodic rhythm, some alliteration and forceful consonants too, to help carry the strength of feeling.

-

3)

A Prophane, Atheistical, Hypocritical, and Hard-hearted, Persecuting, Perverse and Adulterous Generation. (Sandilands 1682)

Linguistic repetition will often find its way into other types of rhetoric, as will be seen in subsequent examples in this paper.

I next turn to the pragmatic concept of speech acts in communication, and specifically directives. Directive speech acts are verbal attempts by speakers or writers to get an addressee(s), namely readers or listeners, to carry out a particular act by, for instance, ordering, exhorting, encouraging, beseeching and so on. Examples in present-day language would be: ‘I beg the government to look at my case’ or ‘let’s go out; exciting things to do near you!’ This excludes THREATENING (see Kohnen 2008: 298 and his study on historical religious language for a fuller linguistic explanation as to why). Manifestations of persuasive language used by Quakers can be found through verbs such as advise and exhort, as well as imperatives that carry a similar directive force. The authors, by a variety of expression, are trying to influence their readers to change their behaviour or their thinking. A dip into the Quaker Historical Corpus for occurrences of WARNING and EXHORTING retrieves these examples (4–7):

-

4)

Therefore feare, feare & repent, repent and prize your time while you have it. (Burrough and Howgill 1655)

-

5)

I advise you in the love of the Lord (O ye of the Parliament, and all others that are called Magistrates), to break off your sins by repentance. (Chandler 1659)

-

6)

I exhort you all to exercise your selves in the law of the Lord, which the Scriptures of truth say is Light. (Bradly 1660)

-

7)

Trades-men, give over deceit and cozening … for to the Lord an account you must give, for everie idle word; therefore now you are warned, take heed of adding to your condemnation, for this is the free love of God to your souls to give you warning, therefore prize it now while you have time. (Harwood 1655)

Warning is a good persuasive strategy to alert people to open their minds to danger and thence to a nudge in the direction of solutions.

Still staying with the strategy of emotional persuasion, we next explore the prophetic mode of ‘predicting trouble’ coupled with unvarnished warning language. This rhetoric employs the conditional syntactical clauses of unless …, except you do …, if you do not …, and so on. See two extracts below (8–9) from the writings of Christopher Fell and, surprisingly late in the century, Joseph Sleigh:

-

8)

And yet thou art filling the measure of thy fathers iniquities, and the same wrath, curse, and judgements of God waites to be poured upon thee, except thou repent, and be warned in time; many warnings hast thou had from the Lord. (C. Fell 1655)

-

9)

So these Priests or Teachers that preach up Sin and Disobedience, they may see their Original, the Serpent; and if they repent not, but continue in their obstinacy, and evil serpentine Doctrine, they will come under the Curse and Indignation of God, as the Serpent did. (Sleigh 1696)

There is a special subset of warning discourse that comes under the heading of Old Testament ‘woe prophecy’ (see Sweeney 2000: 358). Gerstenberger (2012) explains it in these broad terms: ‘The [OT] prophets preserved a form of speech in their writings which announced to groups of evil-doers woe, that is, impending misfortune, doom, destruction because of the specified deeds which had been committed by such evil-doers’ (Gerstenberger 2012: 253). It transpires that some early Quaker writers adopted this ancient form—here are two examples (10–11) from the corpus:

-

10)

Wo, Wo will be to the Blind Guides that wear the long Robes, the false Teachers of this Nation. (Travers 1677)

-

11)

But when you are in the Lake and Pit howling and roaring, then you will know that you were warned in your life-time, and repented not, and to you all this is the eternal word of God, which will surely be fulfilled upon you, you cannot escape, the mouth of the Lord hath spoken it. Woe, woe, woe be unto you, the terrible and dreadful judgements of God powerful and dreadful to the wicked, are coming speedily upon you. (Taylor et al. 1655)

A jeremiad as a type of lamentation is yet another specific text type—a politico-religious sermon, if you will. Murphy explains it thus: ‘the sacred texts of many religious traditions lament declining moral and spiritual standards, and hold out hope for renewal and revival, if only the community will see the error of its ways’ (Murphy 2009: 6). And, to round off this sequence of Quaker examples of emotion-based (pathos) persuasion, example (12), below, combines several devices beautifully: lexical repetition, ‘lest’ conditional warning syntax, the lexical word warning itself and two instances of the word woe.

-

12)

Woe unto all those who stands in opposition against the spirit of truth; I say, eternally woe, and plagues, and misery, from the Lord God will come upon all those that opposeth the Son of God in his appearance; therefore I say, repent, repent, repent, while the door of mercy is open unto you, lest ye be shut out: for without stands dogs; horemongers; adulterers, and all that tells lies; therfore, I say, let this be a warning to you, as from the Lord. (Margaret Abbott 1659)

So far I have located and exemplified numerous features of pathos as a persuasive rhetorical strategy in the QHC. Finding examples based more on logic or reason (Aristotelian logos) is less straightforward. These types of text tend to be published rather later in the century than the more excitable examples presented earlier in this paper. They sometimes include, helpfully for our purposes, the actual words convince or persuade. Here is just one extract illustrative of other similar exhortation writings.

-

13)

All ye that are tender-hearted, and that desires salvation to your soules, come out from among them, and be ye seperate, and touch no unclean thing and I will receive you saith the Lord, for whosoever cannot witnesse Christ Jesus a Saviour from sin in the particular, shall never witness him a Saviour from condemnation, & refuse not to walk with a pure perfect people, … and follow us no farther then as we follow Christ, for we have the mind of Christ; therefore own the light which convinceth you of sin, for as living witnesses for the name of our God do we stand, that the light which convinceth of sin is the true light that leadeth out of sin. (Collens 1685)2

The Deeper Discourse Level of Quaker Persuasiveness

This section presents an analysis of a tract written by Stephen Crisp in 1668: A Plain Path-Way opened To the Simple-Hearted. The purpose of this exercise is to dig deeper than we did with the surface-level linguistic features reported on earlier in the paper. Crisp’s publication is a good example of a gentle but cleverly persuasive text in which the reader is exhorted not to believe some specific doctrine but rather to become open to new possibilities through being guided by the Spirit of God. The hope of such early Friends was that their readers would themselves become convinced.

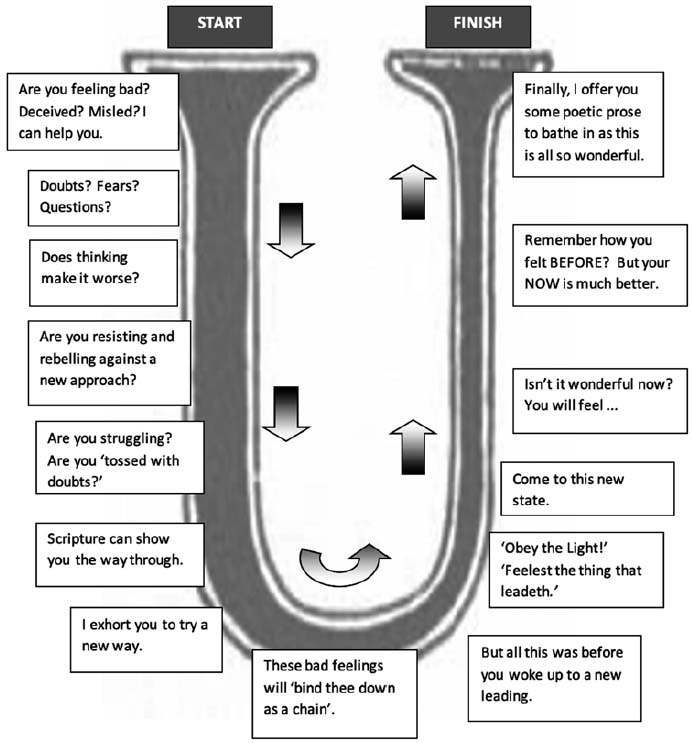

The diagrammatic stages shown in Figure 1 below are not intended in any way to cheapen the strategy that Crisp employed but rather to characterise it in modern ‘sales’ language—sound bites even—as a way in to understanding his approach. I suggest he has discovered an effective method within a seventeenth-century way of thinking, although there can be no way of measuring that today. When the cultural and historical clothing is removed the text is seen to be framed as an effective ‘sales pitch’, in twenty-first-century parlance.

Crisp sets out his purpose clearly right at the start, addressing:

-

14)

… many who are come to feel something stirring and moving in their Hearts (that is good) to bring them into a serious consideration of their course of life, and the inward state of their Immortal Souls … when you have sometimes begun to turn your mind to this good thing that stirred in you, then have many Doubts and Objections arisen in you, lest you should be Mis-led, Deceived or Deluded. (Crisp 1668: 1)

He is hoping to hook those readers who are already feeling uncomfortable and depressed spiritually or, if they have not yet reached that point, might be drawn to identifying with such a state of mind. Much modern advertising uses this approach: see, for instance, a recent article on the power of the ‘anxiety economy’, a present-day version of spiritual unease, by Eva Wiseman in the Observer newspaper, in which she asks: ‘Is anxiety itself being commodified? This is a disorder that can stoke its own fire—worrying about anxiety can make it worse’ (Wiseman 2019). Crisp, in his seventeenth-century way, is offering to ‘expel the clouds of darkness’ so that God’s Light may ‘break forth out of obscurity in which the answer to those Doubts and questions do arise’. Crisp’s part in this is humbly to ‘be a messenger’, he says. (Archangels were traditionally seen as messengers from God.) As marketing discourse is wont to do, the reader is asked if they ‘feel misled, deceived, deluded?’ Crisp adds this with a little dig of emotion (pathos):

-

15)

Now that thou mightst be resolved in such a state what to do, consider thou that hast these struglings in thee about the Light in thy conscience, whether it is true or no, or whether thou shalt own it or no, and art thinking in thy self what is best for thee to do; whether to go on stoutly against it or to submit to it. (Crisp 1668: 4)

We see here he has set up a kind of dialogue with the reader—an effective communicative ploy. His next move is to create binary positions of before and now. Linguists use the term ‘deixis of time’ for this concept, in which a zero point is fixed by the person speaking or writing. For Crisp, before is located temporally as the reader’s probable state of confusion and despair, and now is when the person has been led by the Light and is ready to obey it joyfully. We shall return to these concepts, as they are crucial to his strategy. The author builds up the sense of hopelessness in his potential reader (thou here is in linguistic terms stylistically intimate). The before state is one full of doubts and fears—too late for arguments. We are some way from the logos approach now, in spite of the reassuring biblical reference to Job as a scriptural anchor.

-

16)

Verily I say unto you … before these doubts be resolved, you must try this as, to your Sorrow you have tried the other, before you can be effectually informed; for Arguments will not do sufficiently in this case … They that rebel against the Light, they know not the Way of it; so that if thou dost take that course to rebel, that will but increase thy ignorance of the Way that the Light leads in, and makes it more terrible to thee every time it doth appear in thee, till thou comest to that state spoken of, Job 24:17. That the dawning of the Day will be at the shadow of Death; for the more thou rebelst against it, the more dark thou wilt daily grow, and so the less able to resolve thy self in those doubtful things that fill thy mind; but as Darkness increaseth in thee, so the Power of it will bind thee down as a Chain, and smother every good desire in thee. (Crisp 1668: 4)

The imaginary reader is now nodding and eager to find a solution to these (possibly just-discovered) problems. However, Crisp ratchets up the pressure further:

-

17)

Ye cannot obey this Light of Christ Jesus in your Consciences, but [meaning except] by taking up a daily Cross to your own Wills, Lusts and Affections; for that is contrary thereunto; and that which leads to obey your Lusts, leads to disobey the Light; and that which leads to obey the Light, that crosseth the Lusts and vile Affections, which are at enmity with the Light, and must by it be judged and condemned. (Crisp 1668: 5)

Crisp is ready to offer the relief of a solution to ‘you that are hurried and tossed with Doubts’. He can help make the reader feel better, actually using the word exhortation (which surely translates in present-day English as persuasion or urging) tempered with advice.

-

18)

By that same Spirit that labours with you, am I moved to send this forth unto you all, as a word of Exhortation and Counsel in the Name and fear of the Lord God. (Crisp 1668: 3)

I suggest we are now moving from the before place to an in-between moment of change. The reader is encouraged to submit to the power of the Light in order to avoid being bound down ‘as with a chain’. Verbs such as feel, obey, submit, guided come tumbling out.

We are now at the heart of the discourse and Crisp brings a twist of jeopardy. The reader is presumed now to have tasted the experience of the Light but fails to stay the course and sinks back to the life of before. This is potentially a nail-biting moment, implies Crisp, unless the reader can use that experience and grow through it. Ex. (19) takes us on that part of the journey.

-

19)

When Transgression is finished, then Death enters upon thee with its dark Power, and manifold Sorrows pierceth thy poor Soul; though the fruit was desirable to be eaten, yet now it is eaten, thou canst not come at life, to eat of that too, though thou desirest it; but art driven out, and kept out with a flaming Sword, that turns every way against thee: And here’s now a ground laid for Doubts and Questioning of a higher nature then before, to raise in thee; for before thou doubtedst of the Truth it self, whether it were the Truth, but now having tasted of it, and received a Convincement of it, and yet let forth thy mind from it after other Lovers, & thy ears after the voice of the Adulterers, and so caused the pure Light to withdraw from thee, thorow thy Rebellion now thou desirest thou mightst but see again what thou hast seen, and feel again what thou hast felt, but doubtst & fearst that thou shalt never see, nor feel, nor enjoy the like again, and now thou wishest, O that thou hadst stood in the Cross to thy own will, & that thou hadst denied thy self, that thou mightst not thus have lost the fight and sence of thy Souls Beloved ! And now thou seest by Woful experience whence Doubts and Fears and Sorrows do arise, even thy joyning with the Enemy, who brings forth Reasons against the obedience to the Light. (Crisp 1668: 8)

This writer’s sure touch immediately brings us to a safe place with a phrase familiar to modern readers of Quakerism, a sense of condition. This is Margaret Fell’s insight that the Light will ‘rip you up and lay you open’ (Fell 1656). The reader will find that they no longer have a need of conventional liturgy or church processes [that is, ‘performances’]:

-

20)

Yet there is something remains, which gives thee a sence of thy state and condition, and makes thee to know thy loss and want: hear the voice of this, and this will humble thee, and bring thee into true brokenness of heart, and contriteness of spirit; and as thou comest to know that state, then thou hast something to offer to the Lord of his own preparing, which will be far more acceptable to him then a multitude of Words & Performances & Duties (so called). (Crisp 1668: 8)

From this point in the text we move firmly into the sunny uplands of now. The premise is that the reader at this point will find sweetness and joy and will be the stronger for the period of jeopardy they will have experienced between before and now.

-

21)

Now try and prove whether by taking up thy daily Cross, and obeying of it in thy words and actions, and in all things, if thou dost not find the answer of sweet peace and joy; and when thou shalt find it so, then will there be no more room for doubts and questionings against thy obeying of it; but as any Questions or Doubts do arise in thee, or shall be cast in thy way by any without thee, thou wilt feel the answer of it in thy self to thy refreshing. (Crisp 1668: 10)

The remainder of the 6,000-word tract consists of a poetic confirmation of the rightness of the journey. The persuasiveness will have been effective. There is a going to and forth as the convinced Friend is invited to juggle before and now memories to reinforce the learning. Unlike superficial marketing, where the product is guaranteed to work 100 per cent of the time, this author knows that there must be a continual convincement, a continual lifelong turning to the power of the Light, but the prize in our case is that:

-

22)

When thou comest to know this state, and to receive this White Stone that hath the Name within, thou wilt then be without doubt or fear, given up in the will of God to do and to suffer all things, according to his blessed will. (Crisp 1668: 12)

I hope that the above commentary provides a clear enough road map showing Crisp’s underlying method—namely, a process of guiding and encouraging the reader in his or her experiment in the inwardly guided journey that was to become the ‘Quaker way’; a back and forth between confusion and enlightenment. With no outward help, some encouragement, understanding and persuasion was necessary. All that Crisp clearly provides in his pamphlet. To conclude this section, therefore, I offer a brief tailpiece on some of the lexical items that occur with frequency in Crisp’s text. Setting aside the expected high frequency (111 occurrences) of the group of words for God (God, Light, Lord, Spirit), the next frequency-ranked group—including all word-forms—is DOUBT, KNOW and TRUTH. There are 38 instances of doubt. These include phrases such as doubts and besettings; doubts and questionings; doubts, fears and sorrows; doubts and objections. Crisp knows well how to press the right buttons to demonstrate to the reader that he understands their state of mind.

There are seven instances of REBEL (rebellst, rebellion and so on); interestingly, these all come in the first few pages of the tract. Crisp is assuming that the reader has given up the struggle to avoid a leading and is now submitting to a true inward experience of God. He expresses this frequently (18 occurrences) in the final few pages, using phrases containing the headword WITNESS. Here are two examples:

-

23)

And when the Lord doth thus arise in your Souls, and stir up his own pure Witness, and his Arm awakens in you, and his pure Light breaks forth; Oh! what Consolation is it to you. (Crisp 1668: 6)

-

24)

There is no way for your deliverance but you’re giving up in single obedience to that faithfull and true Witness of God which stirs and moves in thee against thy sins; and therefore wait thou to feel thy mind and will subjected thereunto. (Crisp 1668: 13)

Other key mental or state verbs that Crisp employs in the furtherance of his argument are: KNOW, OBEY and PEEL. There are two frequently occurring nouns in this same semantic area: TRUTH and SOUL. These lexical items are skilfully brought in to the discourse with sufficient repetition and at the right stages of the argument to get the Quaker message across.

To complete the picture, mention must be made of the search for any obvious logos elements in the rhetoric. Any attempt at convincement in terms of one’s soul and its spiritual path is unlikely to be effective if reason alone is used—at least according to the Quaker way. However, there are a few biblical references (for instance, John 1:9 and Job 24:17) and a couple of instances where the word proof occurs—a pointer to the domain of reason. (If Crisp is to use logos effectively he must show he is a credible figure. Apt reference to the Bible is a recognised way to do this at this time.) At the beginning Crisp exhorts the reader to make use and proof of the method he will expound. A few pages on he twice urges the reader to try and prove what this Principle [that is to say, ‘method’] can do for thee. The word PROOF is a nod in the direction of a testing or experimenting rather than attempting to impose an action on the reader. Gentle persuasion, Quaker style.

Conclusion

The act of persuading or of being persuaded must be one of the oldest communicative activities that humankind undertakes. This paper has looked back to these origins—one of the three arts of discourse in antiquity—as promulgated by Aristotle and Cicero, and has framed an understanding of the activity still familiar to us in the present era. Whether possessing knowledge of the ancient world or not, many Friends in the seventeenth century certainly made it their business to seek to convince those around them to try the Quaker Christian path. This paper has explored some of the strategies early Quakers used in order to exhort, influence, urge and entreat ‘all the inhabitants of the world’.

The analysis used two approaches based on a variety of rhetorical strategies: first a surface-level investigation, building on certain theoretical studies attested in the sub-linguistics domains of communication and argument. Simple corpus-based tools retrieved sufficient examples of these devices as illustration of early Friends’ approach to this activity. Most examples are in the field of pathos or emotion, veering into ‘warning’ language and a reliance on fear appeal to convince readers. This style tended to be more favoured by Quaker writers publishing in the later years of the seventeenth century. My corpus-based investigation is, however, not exhaustive and generalisations can be risky. Writings from the later years of the century do appear to show a reduction in the stylistically unrestrained approach of the mid-century. Nevertheless, this period has also given us many more of such mature tracts (if they may be characterised as such) that today’s culture might regard as more worthy of standing the test of time. One such is Stephen Crisp’s 1660s tract analysed in the present paper. This study has brought to light the careful, restrained yet effective approach Crisp employed as encouragement to his reader to at least try this new Quaker way. Crisp was not alone in this initiative. Ambler (2012) has drawn attention to authors writing with a similar message, such as Bathurst, Fell, Fisher, Nayler, Penn and Penington, as well, of course, as George Fox.

So, if we know more now about how Friends went about their attempts to convince, are we able yet to say how effective these strategies were? Today, we would probably design a survey and issue it to as many convinced Friends as we could, asking them where they had heard about Quakerism and what or who persuaded them to try the Quaker way. This is clearly not possible for past eras. We can estimate, not very reliably, how many people identified as Quakers (or Friends of the Truth) in the British Isles of the seventeenth century but we will never know for sure which if any of the tracts, books, broadsides and pamphlets were key to achieving those numbers. As is often said by historical linguists, all historical data is bad data, but unfortunately it is the best we have. The rest must be speculation.

References

Ambler, R., The Quaker Way: a Rediscovery, Winchester: Christian Alternative, 2012.

Bauman, R., Let your Words be Few, London: Quaker Home Service, 2nd edn, 1998.

Bender, J. and Wellbery, D. E. (eds), The Ends of Rhetoric History, Theory, Practice, Redwood City, CA: Stanford University Press, 1990.

Cope, J., ‘Seventeenth-Century Quaker Style’, Modern Language Association of America 71 (4) (1956), pp. 725–754.

Corns, T. and Loewenstein, D., ‘Introduction’, in their The Emergence of Quaker Writing: dissenting literature in seventeenth-century England, London: Frank Cass & Co, 1995, pp. 1–5.

Crespo-García, B., ‘Persuasion markers and ideology in eighteenth century philosophy texts’, Revista de Lenguas para Fines Específicos 17 (2011), pp. 199–228.

Crisp, S., A Plain Path-Way Opened to the Simple-Hearted, 1668. Available at https://www.woodbrooke.org.uk/resource-library/quaker-historical-corpus (QHC40 Crisp. Wing C6938), 1/06/19.https://www.woodbrooke.org.uk/resource-library/quaker-historical-corpus

Dillard, J. P. and Pfau, M., The Persuasion Handbook: Developments in Theory and Practice, Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 2002.

Fell, M., ‘An Epistle to Convinced but not yet Crucified Friends’, in her For Manasseth Ben Israel: the call of the Jewes out of Babylon, London: Giles Calvert, 1656.

Gerstenberger, E., ‘The Woe-oracles of the Prophets’, Journal of Biblical Literature 81 (1962), pp. 249–63; http://geb.uni-giessen.de/geb/volltexte/2012/8808/pdf/Gerstenberger_Woe.pdf [accessed 05/06/19].http://geb.uni-giessen.de/geb/volltexte/2012/8808/pdf/Gerstenberger_Woe.pdf

Green, I., Print and Protestantism in Early Modern England, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000.

Gwyn, D., Apocalypse of the Word: the life and message of George Fox, Richmond, IN: Friends United Press, 1986.

Hagglund, B., ‘Quakers and Print Culture’, in Angell, S. and Dandelion, P., The Oxford Handbook of Quaker Studies, Oxford: OUP, 2013, pp. 477–91.

Halmari, H., ‘In Search of “Successful” Political Persuasion—a comparison of the styles of Bill Clinton and Ronald Reagan’, in Halmari, H. and Virtanen, T. (eds), Persuasion across Genres, Amsterdam: John Benjamins, 2005, pp. 105–34.

Halmari, H. and Virtanen, T. (eds), Persuasion across Genres, Amsterdam: John Benjamins, 2005.

Hill, A. S., The Principles of Rhetoric, New York: Harper & Bros, 1896.

Hill, C., ‘Forerunners of Socialism in the Seventeenth-Century English Revolution’, Marxism Today (September 1977), pp. 270–76; http://banmarchive.org.uk/collections/mt/pdf/09_77_270.pdf [accessed 02/06/19].http://banmarchive.org.uk/collections/mt/pdf/09_77_270.pdf

Hinds, H., George Fox and Early Quaker Culture, Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2011.

Holstun, James (ed.), Pamphlet Wars: prose in the English revolution, London: Frank Cass, 1992.

Jackson, R., ‘The Pragmatics of Repetition, Emphasis and Intensification’, Unpublished thesis, University of Salford, 2016.

Keeble, N. H., ‘The Politic and the Polite in Quaker Prose: the case of William Penn’, in Corns, T. and Lowenstein, D. (eds), The Emergence of Quaker Writing: dissenting literature in seventeenth-century England, London: Keeble, 1995, pp. 112–25.

Kohnen, T., ‘Tracing Directives through Text and Time: towards a methodology of a corpus-based diachronic speech-act analysis’, in Jucker, A. and Taavitsainen, I. (eds), Speech Acts in the History of English, Amsterdam: John Benjamins, 2008, pp. 295–310.

Loewenstein, D. ‘The War of the Lamb: George Fox and the apocalyptic discourse of revolutionary Quakerism’, in Corns, T. and Lowenstein, D. (eds), The Emergence of Quaker Writing: dissenting literature in seventeenth-century England, London: Frank Cass & Co, 1995, pp. 25–41.

Morrissey, M., ‘Scripture, Style and Persuasion in Seventeenth-Century English Theories of Preaching’, Journal of Ecclesiastical History 53 (2002), pp. 686–706.

Murphy, A. R. Prodigal Nation: moral decline and divine punishment from New England to 9/11, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009.

O’Malley, T., ‘“Defying the Powers and Tempering the Spirit”. A Review into Quaker Control over their Publications 1672–1689’, Journal of Ecclesiastical History 33 (1) (1982), pp. 72–88.

OED (Oxford English Dictionary online), Oxford: Oxford University Press, November 2019; https://www.oed.com [accessed 29/10/20].https://www.oed.com

Parry, D., ‘“A Divine Kind of Rhetoric”: rhetorical strategy and spirit-wrought sincerity in English puritan writing’, Christianity and Literature 67 (2017), pp. 113–38; https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/metrics/10.1177/0148333117734162 [accessed 03/11/19].https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/metrics/10.1177/0148333117734162

Peters, K., ‘Patterns of Quaker Authorship, 1652–56’, in Corns, T. and Lowenstein, D. (eds), The Emergence of Quaker Writing: dissenting literature in seventeenth-century England, London: Frank Cass & Co, 1995, pp. 6–24.

Peters, K., Print Culture and the Early Quakers, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005.

Roads, J., ‘The Distinctiveness of Quaker Prose, 1650–1699: a corpus-based enquiry’, unpublished PhD thesis, University of Birmingham, 2015. http://etheses.bham.ac.uk/5938/21/08/2019 [accessed 04/10/20].http://etheses.bham.ac.uk/5938/21/08/2019

Roads, J. (ed.), Quaker Historical Corpus: a collection of machine-readable digitised texts written by Quakers between 1650 and 1690, 2016. https://www.woodbrooke.org.uk/resource-library/quaker-historical-corpus [accessed 02/06/19].https://www.woodbrooke.org.uk/resource-library/quaker-historical-corpus

Roads, J., ‘The Language of Historical Religious Controversies: the Case of George Keith and the Quaker Movement in England’, Journal of Religion in Europe 11 (2018), pp. 46–72; https://brill.com/view/journals/jre/11/1/article-p46_46.xml [accessed 03/08/19].https://brill.com/view/journals/jre/11/1/article-p46_46.xml

Romack, K., ‘For This is the Naked Truth: the early Quakers and going naked as a sign’, The American Journal of Semiotics 27 (2011), pp. 203–31.

Shuger, D. K., ‘Sacred Rhetoric in the Renaissance’, in Heinrich F. Plett (ed.), Renaissance Rhetoric, Berlin, New York: Walter de Gruyter, 1993, pp. 121–42.

Smith, N., Perfection Proclaimed: Language and Radical Religion 1640–1660, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1989.

Smith, N., ‘Hidden Things Brought to Light: Enthusiasm and Quaker discourse’, in Corns, T. and Lowenstein, D. (eds), The Emergence of Quaker Writing: dissenting literature in seventeenth-century England, London: Frank Cass & Co, 1995, pp. 57–69.

Sweeney, M., ‘Micah’, in Sweeney, M. and Cotter, D. W. (eds), The Twelve Prophets, vol. 2, Collegeville, MN: The Liturgical Press, 2000, pp. 359–416.

Tarasheva, E., ‘Repetition of Word Forms in Text: an approach to establishing text structure’, UCREL publications CL2007 paper 82 (2007).

Wiseman, E., Feel Better Now? The Rise and Rise of the Anxiety Economy, 10 March 2019; https://www.theguardian.com/global/2019/mar/10/feel-better-now-the-rise-and-rise-of-the-anxiety-economy [accessed 21/08/19].https://www.theguardian.com/global/2019/mar/10/feel-better-now-the-rise-and-rise-of-the-anxiety-economy

Notes

- This is a pragma-stylistics feature, not an Aristotelian category. For a very technical explanation see Jackson 2016, http://usir.salford.ac.uk/id/eprint/40366/1/pdfcorrectedversionofthesis.pdf [accessed 05/09/20]; or Tarasheva 2007, http://ucrel.lancs.ac.uk/publications/CL2007/paper/82_Paper.pdf). ⮭

- Convincement. Sense 4 in the OED has: ‘Conscientious or religious conviction; conviction of sin; esp. used by Quakers in the sense of religious conversion’. Convincement/conviction—early Quakers’ double meaning of sin and conversion/persuasion. (See Gwyn 1986: 67, ‘Conviction, the pronouncement of guilt. Those who were turned to the light therefore expressed themselves convicted of their sins … convinced not by the preached Word but by the inward Word, to which Quaker preaching turned them.’) ⮭