Introduction

Within seventeenth-century Britain the Religious Society of Friends experienced periods of outright rejection and relative acceptance that shaped the location and form of early sites such as meeting houses and burial grounds. The foundation of burial grounds often preceded the foundation of meeting houses (Laqueur 2015: 299), both of which were sometimes accommodated on land given freely for the purpose by members, while, in other cases, land was purchased specifically (Davies 2000: 80). Quaker burial practices diverged significantly from predominant rites, rejecting Anglican ritual forms while also eschewing the post-medieval period’s increasing focus on mortuary practice as a public performance serving to illustrate or celebrate the status of the deceased (Houlbrooke 1999). Instead, simple services accompanied burial in unconsecrated ground, observed within an aesthetic of plainness devoid of material trappings or accompanying rituals such as feasting, drinking or gift exchange (Davies 2000: 40–42). Within this context of muted observance, a small but consistent minority of burial sites that were purchased rather than donated bear place-names associated with morbid activities, with examples including Golgotha, Gallowgate and Gallows Ditch.

In the present work, two case studies will be explored: the Bunhill Burial Ground in London, the name of which derived from the earlier Bone-Hill (Weil 1992: 77; Garrard and Parham 2011), and Moorside Burial Ground on the outskirts of Lancaster, known locally as Golgotha on account of its proximity to a local site of execution (Fleury 1891: 139). These sites have been selected on the basis of their great significance in early Quaker history, while also offering contrasting accounts of the affective relationships between Quaker burial sites and morbid land uses. Bunhill, for example, was distanced from its past through renaming, while Golgotha at Lancaster remained an active site of criminal execution into the late eighteenth century (Fields 2004: 112), long after the burial ground’s foundation. Further examples will be provided subsequently, supporting the hypothesis of a pattern of association between early Quaker burial grounds and sites that hosted execution via gallows and gibbets. This trend will be analysed, with pathways of interpretation hypothesised and outlined.

As present access to library resources that would illuminate the topic further has been prevented by Covid restrictions, the following work has been presented as a research note in the hope that the present data might prompt further and more exhaustive work in future. Suggestions to this effect are provided in the conclusion.

Case Study One: Bunhill, London

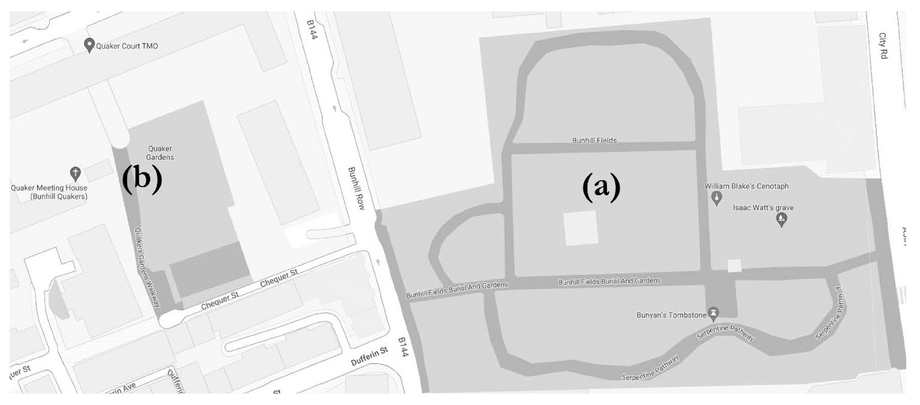

Bunhill is a nonconformist burial ground located in London that grew from a small plot of land on the western edge of Bunhill Fields that was purchased in 1661 by the Religious Society of Friends as its first freehold property in London (Laqueur 2015: 224, Heritage.quaker.org.uk 2021a). Accompanying land was enclosed by the city in 1665 following its proposal as an emergency burial ground for plague dead (Laqueur 2015: 119), although it ultimately did not serve this purpose and remained unconsecrated. The site was thereafter leased to William Tindall, who purposed the land as a dissenter’s burial ground known as ‘Tindall’s Burying Ground’ from 1668 onward (Jones 1848: 6, Holmes 1896: 134). Ultimately hosting the graves of nonconformist luminaries such as Bunyan, Defoe, Blake and John Foxe (Laqueur 2015: 119), Bunhill found recognition as the ‘Campo-Santo of dissent’ (Southey 1830: lxxxi), serving as London’s principal Quaker burial ground until its closure in 1855. Significantly, it is also the resting place of George Fox (d. 1691) and accommodates an associated meeting house that was established in 1950 within a repurposed nineteenth-century caretaker’s house (Heritage.quaker.org.uk 2021a) (Fig. 1).

While the site’s early history is unclear it is believed to have hosted Saxon burials, though by the fifteenth century the area was an unprofitable marsh known as Finsbury Fields that served as a practice area for the city’s archers (Reed 1893: 7–8). Bunhill’s development into the burial ground that is known today commenced in the mid sixteenth century. During the Dissolution of the Monasteries Catholic chantry chapels wherein prayers could be commissioned for a fee from dedicated priests in order to grant relief to souls in purgatory (Roffey 2017) drew the attention of reformers. Chantries were formally dissolved and confiscated by the crown under the first parliament of Edward VI in December 1547 (Houlbrooke 2000: 117), following which they were inventoried and liquidated (Kitching 1980, Woodward 1982). While some were demolished or left to ruin, others were sold into private hands and repurposed as domestic dwellings, storehouses or grammar schools, among other purposes (Roffey 2017: 169–73). These structures often accommodated semi-subterranean charnel chambers, where bones exhumed from crowded churchyards were redeposited in order to free up burial space (Curl 1980: 72), with St Paul’s Cathedral’s chantry chapel having housed the country’s largest charnel (Houlbrooke 2000: 332).

When chantry chapels were sold into private hands the clearance of associated charnel chambers frequently occurred (Curl 1980: 136). This facilitated their repurposing by freeing up space through both stories of the structures. Following the sale of St Paul’s Cathedral’s precinct to the duke of Somerset, in 1549 the charnel chapel was sold on to the stationer Reyner Wolfe, who proceeded to clear the property of remains so that it might be repurposed as a print shop (Kisery 2012: 373). Wolfe described the process to the contemporary antiquarian John Stow, who recorded his account of how ‘more than one thousand cart loads’ of remains were removed to Finsbury Fields and shortly thereafter covered over by ‘soylage of the citie’ (Stow 1633: 356). This generated such a mound that three windmills (later six) were erected on the site to take advantage of the raised terrain (Buckland 1988). The site was further augmented throughout ongoing Elizabethan charnel clearances (Curl 1980: 136), while also serving as a place of burial for heretics (Holmes 1896: 134).

As a result of this process, the site became known as ‘Bone Hill’, in reference to the literal hill of human bones that had been created there (Weil 1992: 77; Garrard and Parham 2011). This, in addition to the accommodation of heretic burials, evidences the site’s marginal status prior to its formal enclosure as a burial ground in the mid seventeenth century. By the early eighteenth century ‘Tindall’s Burial Ground’ was commonly known as Bunhill, a corruption of the earlier ‘Bone Hill’. This shift in name and status is attested by the 1717 publication of Edmund Curll’s ‘The Inscriptions Upon the Tombs, Grave-Stones, &c. In the Dissenters Burial Place Near Bunhill-Fields’, evidencing the site’s accepted nonconformist status and popular regard. Through this nominal shift, the site was disassociated from the morbid connotations of its prior use.

Case Study Two: Golgotha, Lancaster

Lancaster’s meeting house was established in 1677 following the prior foundation of a burial ground to the east of the city on Lancaster Moor c.1660–61. A further burial ground attached to the meeting house was additionally employed between 1694 and 1940 (Gedge 2000: 15; Heritage.quaker.org.uk 2021b). Moorside burial ground is presently situated alongside Wyresdale Road and is one of the earliest sites associated with religious nonconformity in Lancaster (Lancaster.gov.uk 2016), as well as one of the oldest Quaker burial grounds in general (Sayer 2011a: 206). In spite of this, the site has remained understudied and is presently overgrown.

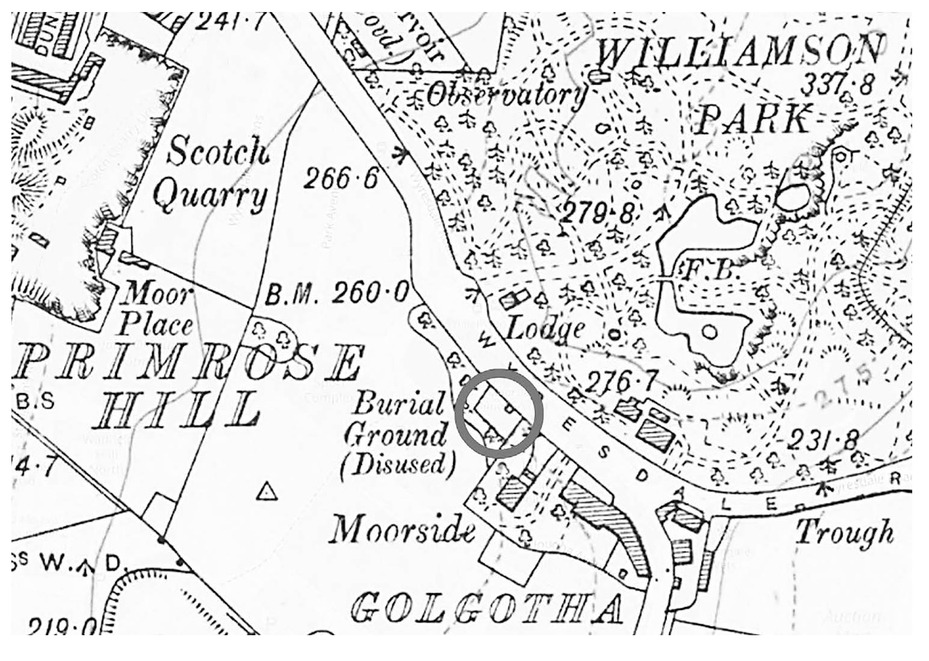

The burial ground is surrounded by a high wall set back from the road with no dedicated access path or explanatory signage, although its gate remains accessible (Fig. 2). The site is close to a small collection of domestic dwellings known as ‘Golgotha Village’, which takes its name from its proximity to the Lancaster Moor execution site (Fleury 1891: 139), which was located on the hill now occupied by Williamson Park (Fig. 3). Prior to the relocation of executions to Lancaster Castle in 1796, Golgotha hosted executions of criminals from across Lancashire, owing to the castle’s accommodation of Lancaster’s County Assize (Fields 2004: 112, Marsden 2018). The remnants of a set of stone stocks are situated at the side of the road a short distance from the burial ground’s entrance. Local folklore asserts that the bodies of executed criminals were buried at the site prior to its acquisition by the Religious Society of Friends, although no evidence supports this belief (Lancaster City Museum 2020). However, the punitive burial of at least one suicide is known to have occurred on the Moor in the 1790s (Tarlow 2017: 17).

Positioning of Moorside burial ground (circled) in relation to Lancaster’s former execution site (occupied by Williamson Park) and Golgotha village, bottom right. Circa 1888–1913. Source: OpenStreetMapFoundation via National Library of Scotland. © OpenStreetMap contributors. Licence: Open Database Commons (ODBL) v1.0 / CC BY-SA 2.0.

Because of its status as a venue of county-wide executions, Lancaster Moor was a notorious marginal landscape in medieval and post-medieval north-west England, with ongoing popular infamy deriving from its hosting the execution of the Pendle Witches in 1612 (Clark 2009: 58). This reputation manifests in the area’s identification as ‘Golgotha’, after the site of Christ’s crucifixion. Executions continued there until the late eighteenth century, long after the c.1660–61 foundation of the Quaker burial ground. Notably, this example differs from Bunhill, where prior morbid land use was effectively erased through its nominal shift from ‘Bone Hill’ to ‘Tindall’s Burying Ground’ before ‘Bunhill’ became predominant. Moorside Burial Ground at Lancaster, conversely, remained lastingly identified as ‘Golgotha’ and existed in close proximity to an active site of criminal execution for over a century before judiciary activities were relocated, with the affective presence of morbid associations in the landscape remaining both historically and contemporarily profound (Tarlow and Dyndor 2015: 71).

Further Sites and Analysis

In the two case studies provided, the morbid naming of seventeenth-century Quaker burial grounds derived from prior and ongoing uses of acquired land. Bunhill derives from Bone Hill on account of the site hosting a vast quantity of human remains that were redeposited on unconsecrated ground during the reformation’s largest single disturbance of remains and monuments (Marshall 2002: 107), while Lancaster’s Golgotha was so known on account of its close proximity to a notorious and active site of criminal execution. Both sites are of significance within early Quaker history, with the Friends’ burial ground at Bunhill representing the Society’s first freehold of land within London and Golgotha being situated in the heart of the 1652 Country and one of the earliest sites of nonconformist religious practice in Lancaster (lancaster.gov.uk 2016).

In addition to these sites, similarly morbid components of inherited place-naming are to be found in the seventeenth-century Quaker establishments at Gallowgate in Aberdeen (1672), Gallows Ditch at Hillworth (1665) and Gibbet Street in Highroad Well (1693). While these sites have been readily identified through the extant nature of their morbid naming in association with gallows and gibbet sites, it is highly likely that in other instances changes in nomenclature over time have rendered similar historical connections more difficult to establish. The etymology of Bunhill, for instance, is familiar to the author owing to prior site-specific research (see Farrow 2020, forthcoming), while awareness of Golgotha is similarly circumstantial, resulting from the author having lived in Lancaster as an undergraduate. Uncovering more examples of similar nomenclature would require an exhaustive survey of seventeenth-century Quaker burial grounds in relation to local geographical and etymological histories. It is envisioned that combining data gleaned from David Butler’s ‘The Quaker Meeting Houses of Britain’ (1999) with local history approaches would prove to be of inestimable value in this task.

When interpreting the significance of this pattern it is important to acknowledge that undesirable, taboo or marginal properties may have been easier and cheaper to obtain than alternative sites within the context of Quakerism’s seventeenth-century controversy. However, it might also be the case that the indiscriminate employment of these spaces would have held conceptual relevance within the context of their foundation. With Quakers themselves occupying a liminal position within seventeenth-century society, characterised by social participation while maintaining separation from its vices—that is, being ‘in the world, but not of it’ (Tolles 1960: 75)—the occupation of liminal spaces could be interpreted as a reflection of this status within the landscape. George Fox’s contemplations in ‘lonesome places’ (Fox 1952: 9) demonstrate that the embrace of liminal spaces holds precedent within early Quakerism, with Fox’s pivotal 1652 vision on Pendle Hill, overlooking Lancaster, providing one potent and relevant example (Fox 1952: 103–104).

Furthermore, owing to the Quaker conception of God as existing within all individuals (Chenoweth 2009: 321, 325) and by extension all places they inhabit, could sites of execution have been perceived as less abhorrent to early Quakers and therefore dually convenient, as sites that could be acquired at reduced cost while potently illustrating the omnipresence of God in spite of earthly corruption? Quaker willingness to bury the dead in unconsecrated ground was justified by a belief in the notion that ‘all ground was God’s’ (O’Donnell 2015: 47), with priority placed on the avoidance of land ‘polluted’ by association with ‘idolising’ Anglican ritual (Davies 2000: 40, 79). It would therefore stand to reason that the more undesirable the land, or rather the further away it was from conventional ideas of consecration, the more effectively its use would state or preach this belief. With the renaming of land acknowledged as a ‘way of creating new connections between the past and the present’ (Alderman 2008: 195), the retention of morbid nomenclature suggests a conscious unwillingness to surrender connotations of marginality in the landscape.

In an epistle of 1669 Fox wrote that Friends should seek to procure ‘convenient burying places … that thereby a testimony may stand against the superstitious idolising of those places called holy ground’ (Fox 1848: 128). While written with reference to Anglican ‘superstition’, acquiring land that held folkloric associations with the supernatural through the proximity of gallows or gibbet (Coolen 2016, Davies and Matteoni 2017) could be interpreted as offering a broader progressive statement within local folkloric as well as national religious cultures. By this means, in addition to satisfying convenience through reduced value, the specific acquisition of morbid sites would have offered locally resonant statements of ideology.

The choice of land in service of ideological statement finds further contextual support within post-medieval burial culture, where funerary practice served as an increasingly ‘charged social signifier’ (Chenowerth 2009: 330) that often employed the elaboration of burial ritual as a means of reinforcing the status of the deceased (Houlbrooke 1999). On this basis, carrying out simple burials on marginal property would have manifested as a particularly strong rebuttal and counter to mainstream practices, rendering Quaker ideology visible and effectively preaching through the landscape. In this way, the consequences of land selection, which may or may not have been initially incidental to economic factors, acquired their own rich symbolic implications through active employment.

Practical motivations in burial site selection have previously been considered by Bashford and Sibun (2007: 102), who noted that in Northamptonshire the purchase of orchards was favoured for the foundation of Quaker burial grounds owing to the prospective economic stability that they granted, as setting a portion of the land aside for burial while leasing the rest would generate funds to maintain the burial ground and other Quaker properties. The fact that prior land use was a central factor of acquisition in these cases suggests that economy might be employed more broadly as the basis for a typology of early Quaker property acquisition. While Bashford and Sibun’s findings indicate that prospects of future economic stability were a primary factor in the ‘orchard’ site type, the reduced value of land associated with morbid practices could be interpreted as a response to more immediate economic concerns, with taboo properties more affordable and therefore ‘convenient’ in line with Fox’s suggestion (Fox 1848: 128).

Further to investigating how early Quakers might have perceived land acquired for religious observation and burial, it is also worth considering how the acquisition and employment of such land would have impacted their contemporary perception within local community contexts. With the term ‘Quaker’ deriving from a mocking characterisation of individuals who would ‘tremble in the way of the Lord’ (Fox 1952: 58), contemporary connotations of stoicism, austerity and marginality could conceivably have been reinforced by the conduct of religious practice and burial in places with such affectively charged names as Golgotha and Gallows Ditch.

Conclusion

The present work has offered evidence of a pattern of morbid inherited place-names in association with a significant minority of seventeenth-century Quaker sites in Britain. These results were presented through a combination of specific case studies and suggestions for further candidate sites, while frameworks of interpretation and significance were proposed and explored. As the location of post-medieval burial grounds in relation to land use and settlement patterns within local religious geographies is an area of ongoing research (Mytum 2004: 17), development of this hypothesis and dedicated research methodologies would bear consequence within broader mortuary and settlement archaeology as well as Quaker studies.

As post-medieval British nonconformist sites have so far received limited archaeological attention (Sayer 2011b: 115), advanced study of Quaker burial sites in particular holds the potential to facilitate nuanced reinterpretation of some of the most important religious developments of the early modern period. Work along these lines would provide insight into early Quaker motivations of property acquisition in addition to revealing how these developments may have influenced the social perception of emerging Quaker communities as marginal groups within seventeenth-century Britain. While further development of this investigation has been hampered by a lack of access to physical documentary resources owing to the ongoing Covid pandemic, it is hoped that the presentation of available data and the proposal of interpretative frameworks will serve as a basis for future and more exhaustive investigation of the given hypothesis.

References

Alderman, D. H., ‘Place, Naming and the Interpretation of Cultural Landscapes’, in Graham, B. and Howard, P. (eds), The Ashgate Research Companion to Heritage and Identity, Aldershot: Ashgate Publishing Limited, 2008, pp. 195–213.

Bashford, L. and Sibun, L., ‘Excavations at the Quaker Burial Ground, Kingston-upon-Thames, London’, Post-Medieval Archaeology 41/1 (2007), pp. 100–54.

Buckland, J. S. P., ‘Technical Notes on 16th and 17th Century London Windmills’, Transactions of the Newcomen Society 60/1 (1988), pp. 127–36.

Butler, D., The Quaker Meeting Houses of Britain, London: Friends Historical Society, 1999.

Chenoweth, J. M., ‘Social Identity, Material Culture and the Archaeology of Religion: Quaker practices in context’, Journal of Social Archaeology 9/3 (2009), pp. 319–40.

Clark, R., Capital Punishment in Britain, Hersham: Ian Allen Publishing, 2009.

Coolen, J., ‘Gallows, Cairns and Things: a study of tentative gallows sites in Shetland’, Debating the Thing in the North: The Assembly Project II: Journal of the North Atlantic—Special Volume 8 (2016), pp. 93–114.

Curl, J. S., A Celebration of Death: an introduction to some of the buildings, monuments and settings of funerary architecture in the Western European tradition, London: Constable, 1980.

Davies, A., The Quakers in English Society 1655–1725, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2000.

Davies, O. and Matteoni, F., Executing Magic in the Modern Era: criminal bodies and the gallows in popular medicine. Hatfield: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017.

Farrow, T., ‘Dry Bones Live: a brief history of English charnel houses, 1300–1900AD’, EPOCH 1 (2000), pp. 16–25.

Farrow, T., ‘The Dissolution of St. Paul’s Charnel: remembering and forgetting the collective dead in late medieval and early modern England’, Mortality (forthcoming).

Fields, K., Lancashire Magic and Mystery: secrets of the red rose county, Cheshire: Sigma Leisure, 2004.

Fleury, C., Historic Notes on the Ancient Borough of Lancaster, Lancaster: Eaton & Bulfield, 1891.

Fox, G., ‘No. CCLXIV’, in Tuke, S. (ed.), Selections from the Epistles of George Fox: second edition with additions, London: Edward Marsh, 1848, pp. 120–30.

Fox, G., in Nickalls, J. L. (ed.), The Journal of George Fox, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1952.

Garrard, D. and Parham, H., ‘Listing Bunhill Fields: a descent into dissent’, Conservation Bulletin 66 (2011), pp. 18–20.

Gedge, P., ‘The Churches of Lancaster—their contribution to the landscape’, Contrebis 25 (2000), pp. 15–20.

Holmes, B., The London Burial Grounds: notes on their history from the earliest times to the present day, New York: Macmillan and Co., 1896.

Houlbrooke, R., ‘The Age of Decency: 1660–1760’, in Jupp, P. C. and Gittings, C. (eds), Death in England, Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1999, pp. 174–201.

Houlbrooke, R., Death, Religion and the Family in England 1480–1750, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2000.

Heritage.quaker.org.uk, Friends Meeting House, Bunhill Fields, 2021a, http://heritage.quaker.org.uk/files/Bunhill%20Fields%20LM.pdf [accessed 12/02/21].http://heritage.quaker.org.uk/files/Bunhill%20Fields%20LM.pdf

Heritage.quaker.org.uk, Friends Meeting House, Lancaster, 2021b, http://heritage.quaker.org.uk/files/Lancaster%20LM.pdf [accessed 12/02/21].http://heritage.quaker.org.uk/files/Lancaster%20LM.pdf

Jones, J. A., Bunhill Memorials, London: James Paul, 1848.

Kisery, A., ‘An Author and a Bookshop: publishing Marlowe’s remains at the Black Bear’, Philological Quarterly 19/3 (2012), pp. 361–92.

Kitching, C. J. (ed.), London and Middlesex Chantry Certificate, London: London Record Society, 1980.

Laqueur, T., The Work of the Dead, Princeton, NJ, and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2015.

Lancaster City Museum, Moorside Burial Ground, Golgotha, 2020, http://www.facebook.com/lancastercitymuseum/posts/567469763797594 [accessed 12/02/21].http://www.facebook.com/lancastercitymuseum/posts/567469763797594

Lancaster.gov.uk, East Lancaster Local List of Heritage Assets, 2016 [accessed 12/02/21], http://www.lancaster.gov.uk/assets/attach/1770/East_Lancaster_Local_List_Nov2016.pdf.http://www.lancaster.gov.uk/assets/attach/1770/East_Lancaster_Local_List_Nov2016.pdf

Marsden, A., Golgotha Village, Lancaster, 2018, https://martintop.org.uk/blog/golgotha-village-lancaster [accessed 12/02/21].https://martintop.org.uk/blog/golgotha-village-lancaster

Marshall, P., Beliefs and the Dead in Reformation England, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002.

Mytum, H., Mortuary Monuments and Burial Ground of the Historic Period, New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers, 2004.

O’Donnell, P. C., ‘This Side of the Grave: navigating the Quaker plainness testimony in London and Philadelphia in the eighteenth century’, Winterthur Portfolio 49/1 (2015), pp. 29–54.

Reed, C., History of the Bunhill Fields Burial Ground, London: Charles Skipper and East, 1893.

Roffey, S., Chantry Chapels and Medieval Strategies for the Afterlife, Stroud: The History Press, 2017.

Sayer, D., ‘The Organization of Post-Medieval Churchyards, Cemeteries and Grave Plots: variation and religious identity as seen in Protestant burial provision’, in King, C. and Sayer, D. (eds), The Archaeology of Post-Medieval Religion, Woodbridge: The Boydell Press, 2011a, pp. 199–214.

Sayer, D., ‘Death and the Dissenter: group identity and stylistic simplicity as witnessed in nineteenth-century nonconformist gravestones’, Historical Archaeology 45/4 (2011b), pp. 115–34.

Southey, R. (ed.), The Pilgrim’s Progress with a Life of John Bunyan, London: John Murray, 1830.

Stow, J., The Survey of London, London: Elizabeth Purslow, 1633.

Tarlow, S., The Golden and Ghoulish Age of the Gibbet in Britain, London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017.

Tarlow, S. and Dyndor, Z., ‘The Landscape of the Gibbet’, Landscape History 36/1 (2015), pp. 71–88.

Tolles, F. B., Quakers and the Atlantic Culture, New York: Macmillan, 1960.

Weil, T., The Cemetery Book, New York: Barnes & Noble, 1992.

Woodward, G. H. (ed.), Calendar of Somerset Chantry Grants, 1548–1603, Taunton: Somerset Record Society, 1982.