In the history of Haverford College, perhaps no figure looms as large as Isaac Sharpless. Sharpless, who served as Haverford’s longest-tenured president, from 1887 to 1917, is generally regarded as a transcendental figure in the history of the college. As president, Sharpless challenged the Quietest Quaker theology that was popular at the time and encouraged Haverford to end its reclusion from worldly affairs.2 As a result, his presidency saw Haverford break many Quaker taboos, such as a rejection of literature and music on campus, and welcome an increasing number of non-Friends to campus.3 This set the stage for an era in which Haverford’s religious mission, though still rooted in Quakerism, took on a more universalistic stance than it had previously.

Yet, as this essay will show, this redefinition of the college’s religious mission developed within the carefully circumscribed limits of white Protestantism. Sharpless articulated a vision for the college that allowed it to maintain its Quaker identity even as Episcopalians and Presbyterians progressively outnumbered Friends in the student body. As a result, Haverford managed to redefine its mission to cater to privileged white Protestants without exposing itself to students from socially undesirable Catholic, Black, and Jewish families. This essay explores these developments in two parts. First, it demonstrates that Sharpless unapologetically considered Haverford a Christian college and that his understanding of this term excluded non-white, non-Protestant groups such as Catholics and Black Christians, though he tolerated a small Jewish presence on campus. Then it uses demographic data to argue that the redefinition of Haverford’s religious mission reflected a larger change in which the college increasingly catered to the sons of the white Protestant elite. The essay concludes with a reflection that calls for a more critical understanding of the relationship between Haverford and the Religious Society of Friends.

No Religious Census: Protestant Ecumenicalism and Its Limits

Over his thirty-year tenure as president, Sharpless repeatedly defined Haverford’s religious mission as both denominationally Quaker and ecumenically Protestant. In 1890 he wrote, ‘It is possible to have a college very useful, and very fair externally, which is wholly secular. I do not think Haverford should ever be allowed to become, by purpose or by drift, such a college.’ Elaborating on this point, he made clear that Haverford should have two aims in its religious education:

In the first place, we should strengthen the loyalty and usefulness to our Church [the Religious Society of Friends] of its own members who come under our influence, impressing them with its spirit and beliefs. In the second place, while not undermining the convictions which attach others to other churches, we must assist and deepen their spiritual knowledge of Christianity.4

In identifying this dual purpose, Sharpless departed from the Quaker tendency to withdraw from the exterior world. His desire to educate across denominational lines marked a new engagement with non-Quaker society that would have been impossible only a generation earlier. However, this notion of religious duty applied only to Quakers’ neighbouring ‘churches’.

Sharpless seemed to consider the education of Christian men to be the primary mission of the college. In fact, from 1902 until 1910, the college catalogue described Haverford as maintaining the traditional ideals of a ‘guarded education’ and religious concern ‘by appeals to Christian principle and manliness, rather than by the exercise of arbitrary power’.5 This focus on Christian education was a hallmark of Sharpless’s presidency. In 1895 he listed Haverford’s attention to ‘the obligations and conditions of Christian living’ as one factor that made the college unique.6 Sharpless reiterated this interest in Christian education throughout his presidency. Most notably, in 1913, he shared his hope that Haverford’s curriculum would ‘attract men who, though not wishing to be professional preachers, still desire their lives to count seriously in Christian work of some kind’.7 In this example, Sharpless made clear that Haverford hoped to attract Christian men, leaving little space in the college’s religious mission for non-Christians.

Unsurprisingly, this focus on Christianity found an expression in the student body. The Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA) was one of the most popular student groups on campus during Sharpless’s presidency. As an international movement, the YMCA incorporated the Protestant ideas of ‘social gospel’ and ‘muscular Christianity’ popular around the turn of the century. College catalogues from the early twentieth century claim that over three-quarters of the student body belonged to the on-campus branch of this organisation.8 Regardless of the exact veracity of this claim, we can conclude that the YMCA held an esteemed presence on campus because, in 1909, Alfred P. Smith ’1884 felt it necessary to reserve space for the organisation in the new Haverford Union Building that he funded. This was evidently not just the fancy of a wealthy donor. Rufus Jones later described the Haverford YMCA as an important spiritual presence on campus during this period.9 Though the foundation of the club predated Sharpless’s presidency, its popularity during his tenure reflected his desire to educate Protestant men.

However, Sharpless’s understanding of the word ‘Christian’ probably excluded both Catholics and Black Christians. Detailed data on the religious affiliation of students do not exist for the Sharpless years, but other evidence suggests his vision for Haverford probably did not include Catholics. In 1905 Sharpless offered a one-sentence reply to a letter from a Catholic intellectual named Charles G. Herbermann who apparently requested information about the number of his coreligionists on the Haverford faculty. Sharpless wrote, ‘In reply to your inquiry of January 30, I would say that there are no Catholics in our faculty.’10 Sharpless’s curt message makes it impossible to conclusively comment on institutional policy towards Catholics.

We can conclude, however, that Haverford was not a supportive environment for Catholics. We have already seen how the YMCA promoted ecumenical Protestant concepts on campus. In addition to the YMCA, the fragment from the college catalogue cited above, which clarified that religious education at Haverford did not appeal to ‘the exercise of arbitrary power’, seems to subtly differentiate between Christian principles at Haverford and in the Catholic Church. The catalogue distinguishes what it sees as true Christian principles from the overbearing Catholic focus on hierarchy and the sacraments.11 Moreover, many Catholics in Philadelphia and elsewhere in America came from immigrant families, which would have made them socially unattractive applicants to Haverford.12 These factors suggest that Sharpless’s curtness may have reflected a wider atmosphere of anti-Catholicism during his presidency and may explain why only four of Haverford’s 208 students identified as Catholic just four years after his retirement.13 Though the paucity of documentation makes it impossible to comment on institutional policies of discrimination under Sharpless, the better-documented anti-Catholic tendencies under his successor William Wistar Comfort—who institutionalised a preference for white Protestant cultural norms in the admissions process and demonstrated a willingness to limit the number of Catholics at Haverford14—reinforce the idea that Sharpless and Comfort did not mean to include non-Protestant Christians such as Catholics when they used the term ‘Christian’.

Sharpless’s opinions on race are just as difficult to pinpoint as his views on Christianity. However, just as in the case of Christianity, the existing evidence suggests the Haverford community did not welcome Black students before World War I.15 Osmond Pitter ’26, the first Black student to attend the college, arrived from Jamaica half a decade after Sharpless had given up the reins to the college.16 Sharpless’s letter books do not preserve his opinion on the admission of Black and African American applicants. Nonetheless, Haverford had no Black or African American students under his watch. One historian’s description of a neighbouring institution, Bryn Mawr College, may adequately describe the situation. She writes that, in 1901, Bryn Mawr president M. Carey Thomas ‘had not faced the issue of the admission of an African-American student to Bryn Mawr College because nonwhite young women simply knew better than to apply’.17 Though Haverford was not entirely white—the college welcomed a select few non-white students, mostly from outside the United States—the notable absence of Black students before World War I demonstrates the boundaries of its newfound inclusivity.

Sharpless’s views on Jews, whose status as a racial or religious group fluctuated over time, are even more difficult to evaluate than his thoughts on Christianity and race.18 His understanding of Haverford as an institution dedicated to the education of Protestant boys seems to preclude Jews. However, we must weigh this understanding against the reality that Sharpless almost certainly admitted the college’s first Jewish students. Elias N. Rabinowitz ’03, the earliest known Jewish student at Haverford, arrived as a freshman in 1899. I have identified three other Jews who studied at Haverford during the Sharpless years, though this number should not be taken as definitive. Although Sharpless never admitted a large number of Jews, the decision to admit any Jews suggests he saw at least a marginal place for them at Haverford. His successors took a less ambiguous stance. Most notably, by 1931, the college had established a quota of three Jewish students per class that remained in effect until at least the early 1940s.19 Though the historical record does not indicate that Sharpless supported such a policy, his vision for Haverford as an institution dedicated to the education of white Protestant boys paved the way for his successors to adopt antisemitic admissions policies.

It is important to remember that Sharpless’s ecumenical message significantly altered Haverford’s Quaker character without destroying or totally departing from it. For Sharpless, the fusion of Christian ecumenicalism and Quaker distinctiveness defined Haverford. Writing after his retirement in 1917, he offered six ideals that guided his administration. The second point unambiguously stated, ‘Haverford makes no claims to being undenominational’ and cites compulsory Quaker Meeting as a distinctive part of the college’s identity. Yet, Sharpless hedged this claim of sectarian identity with a reminder that Haverford ‘takes no religious census’. The juxtaposition of these two claims points to the tension between Quaker distinctiveness and the desire to engage with worldly affairs that partially characterised Sharpless’s presidency. He resolved this tension by appealing to Haverford’s Quaker founders. He argued, ‘The objects of the founders are perhaps more surely gained by this broader experience [of welcoming non-Friends] in college life than by the exclusive methods of early days.’20 According to Sharpless, Haverford could redefine its mission and educate men of different religious backgrounds while still realising the college’s original goal, which he described earlier in the same book as ‘frankly denominational’.21 This rhetorical wrinkle highlights the fact that Sharpless considerably expanded the accepted understanding of Haverford’s Quaker character, though it still excluded Catholic, Black, and Jewish young men and others who were not white Protestants. Perhaps more important to Sharpless was the fact that presenting Haverford’s Quaker character as amenable to outside churches meant the college could retain its Quaker identity even as Episcopalians and Presbyterians became the predominant religious groups in the student body.

Demographic Changes: The Episcopalian and Presbyterian Elite Arrive

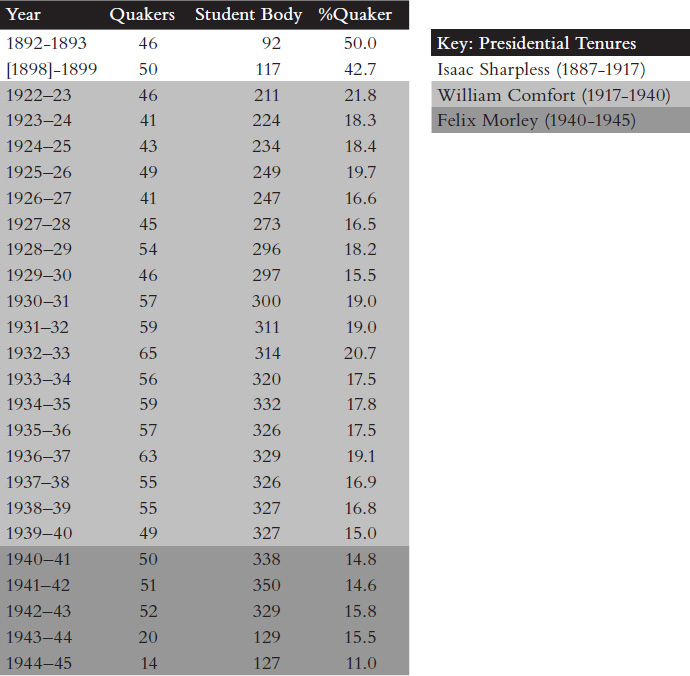

The more inclusive conception of Haverford’s Quaker character, working in conjunction with the transformative agenda pursued under Sharpless, produced noticeable changes on campus. Sharpless’s modernisation plan called for and resulted in significant growth of the student body, which more than doubled in size during his presidency.22 This growth resulted in a significant decrease in the percentage of Friends in the student body (Chart 1). For instance, the student body was evenly split, with 46 Friends and 46 non-Friends, during the 1892–93 academic year, but by the 1898–99 year the number of non-Friends had increased to 67, while the number of Friends rose just slightly to 50. This trend continued beyond the Sharpless years. Whereas 42 per cent of students were Quaker in 1898, the percentage of Friends in the student body slowly fell until they represented just 15 per cent of students in 1940. In other words, the actual number of Quaker students at Haverford remained nearly constant from the late nineteenth century until the eve of the Second World War, even though the overall number of students more than doubled during that span. Even a small increase in the percentage of Friends during the 1930s could not bring Quakers back to the level they reached in 1922–23, the first year of the twentieth century for which we have data. The gradual decrease in the percentage of Friends in the student body was accompanied by an increased presence of Presbyterians and Episcopalians. By 1922, these two denominations, which were closely associated with the Philadelphia elite, accounted for almost half of all Haverford students.23 The combination of these demographic trends and the broadened definition of Haverford’s religious mission promoted by Sharpless reflect a major transformation in the type of student the college sought to attract.

Quakers as a Percentage of Haverford Students, 1892–1945.24

Beginning in the late nineteenth century, Haverford increasingly catered to the sons of the elite. Sharpless claimed this development predated his appointment as president and that the Board of Managers emphasised the protection of this constituency in their presidential search.25 If this is true, they must have been pleased with their decision. Although his academic vision inspired Sharpless to dismiss the unproductive sons of the elite, his vision for Haverford left ample room for the mostly Episcopalian and Presbyterian Philadelphia elite without exposing the college to students from less socially desirable Catholic, Black, and Jewish backgrounds. As a result, privileged white Protestants from the upper-middle and upper classes replaced Quakers as the college’s main clientele.26

Haverford’s transformation into a school for the white Protestant elite significantly improved its reputation. Haverford spent most of the nineteenth century as a prestigious institution within the Gurneyite segment of the Society of Friends, but on the eve of World War II it had become recognisable among the Philadelphia upper class. Sociologist E. Digby Baltzell estimated that by 1940 Haverford and Swarthmore were collectively the fifth most prestigious institutions among the Philadelphia upper class. Although these two colleges originally belonged to different branches of the Society of Friends, Baltzell and many non-Quakers did not distinguish between them based on the internal divisions among Friends. For these people, Haverford and Swarthmore were Quaker colleges whose prestige came in behind Harvard, Princeton, Yale and a conglomerate of out-of-state schools but ahead of all other Philadelphia institutions. Haverford had become one of the most prestigious colleges in Philadelphia. Although the college’s well-known relationship with Harvard probably contributed to its image, we should not discount the influence of the increasing interaction between elite Quakers and other white Protestants in improving its reputation. According to Baltzell, Quaker and white Protestant elites began to intermingle at the end of the nineteenth century.27 This intermingling meant that an elite Quaker college such as Haverford could integrate itself into the larger white Protestant elite. Changing the profile of the college also offered Haverford an opportunity to protect itself from the demographic decline among Philadelphia Friends that took place in the nineteenth century.28 Thus, the education of non-Quakers may have been necessary in order to attract enough students to remain viable. As a result, however, Haverford permanently sacrificed having a Quaker majority among its students.

Conclusion: Becoming a Patrician Institution

This essay has focused on how Isaac Sharpless redefined Haverford’s religious mission so that the college could accommodate the sons of privileged white Protestants without losing its Quaker identity. I have demonstrated the effect of this redefinition by paying close attention to changes in the student body both during and after the Sharpless years. We must remember, however, that students formed only one part of a larger symphony of institutional players. Haverford, like other colleges and universities, was a dynamic institution with students, alumni, faculty and a Board of Managers each jockeying for power within the institution. Though the Board and presidency remained stalwarts of Quakerism at Haverford until after World War II, the college gradually became more patrician and less Friendly. Former president of the college Felix Morley—whose father served on the faculty under Sharpless and who graduated from Haverford in the final years of the great president’s tenure—aptly described the long-term effect of these trends when he recalled the institution that he inherited in 1940:

Haverford had drifted some distance from its original Quaker moorings … . But in doing so it had become Ivy League rather than democratic. There were no Negroes, few Jews or Romans [Catholics] and scarcely any proletarians in the enrollment. It was a WASP institution—White, Anglo-Saxon, Protestant—quite wealthy and somewhat smug.29

Morley calls attention to a question that has sat at the centre of many debates at Haverford, but that has often been overlooked in descriptions of it: to what extent is it accurate to describe Haverford as a Quaker college?

Notes

- This essay was adapted from my undergraduate thesis. I would like to thank Dr James Krippner and Dr Linda Gerstein for their mentorship on that project as well as Dr David Harrington Watt, whose insights have proved critical in the development of this paper. ⮭

- See Sharpless, I., The Story of a Small College, Philadelphia: John C. Winston, 1918; Krippner, J., and Watt, D. H., ‘Henry Cadbury and His World’, in Henry J. Cadbury, Leiden: Brill, forthcoming; Bronner, E., ‘The Sharpless Years’, in Kannerstein, G., (ed.), Spirit and the Intellect: Haverford College, 1833–1983, Haverford, PA: Haverford College, 1983, pp. 23–30; Benjamin, P., The Philadelphia Quakers in the Industrial Age, 1865–1920, Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1976, pp. 41–48. ⮭

- Benjamin, Philadelphia Quakers, pp. 46–47. ⮭

- Sharpless, Story, pp. 182–83. ⮭

- ‘History and Description’, Haverford College Bulletin (HCB) Vols 1–9, New Series. All references to the Bulletin are to the New Series. ⮭

- Sharpless, Story, p. 190. ⮭

- Sharpless, Story, p. 212. ⮭

- HCB, Vols 2–8. The YMCA is usually listed under ‘Societies’ in the catalogue. ⮭

- ‘Annual Report of the Board of Managers’, HCB 9, no. 2 (October 1910), p. 8. Sharpless, Story, p. 163; Jones, R., Haverford College: A History and an Interpretation, New York: Macmillan, 1933, p. 57. See also Comfort, W. W., ‘Autobiography’, William Wistar Comfort Papers, Quaker and Special Collections at Haverford College (QSC), p. 28a. ⮭

- Sharpless to Hebermann, 1 February 1905, Letterbook, 1904–1905, Isaac Sharpless Presidential Papers, QSC, p. 222. ⮭

- ‘History and Description’, HCB 1–9. ⮭

- Rzeznik, T., ‘Roman Catholic Parishes’, in Mires, C., et al. (eds), The Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia, Camden, NJ: Mid-Atlantic Regional Center for the Humanities, 2017, https://philadelphiaencyclopedia.org/archive/roman-catholic-parishes/ (accessed 24/03/2022); Klaczynska, B., ‘Immigration (1870–1930)’, in Mires et al., Greater Philadelphia, 2014, https://philadelphiaencyclopedia.org/archive/immigration-1870-1930/ (accessed 24/03/2022). ⮭

- Comfort, W. W., ‘President’s Report’, HCB 21, no. 2 (November 1922), p. 10. ⮭

- Unknown to Julian Mack, 5 March 1931, HCHC Year Boxes (unfiled), Box 10, 1931, QSC. I would like to thank Elizabeth Jones-Minsinger for helping me locate this letter. ⮭

- I intentionally use the word Black instead of African American because Haverford’s first Black student was not from the United States. The earliest known African American student at Haverford was David Johnson ’47. This distinction does not reflect the terminology of archival sources, which usually refer to the students I identify as Black or African American as ‘Negroes’. ⮭

- See also Williams, Jr., A., and Brown, C. F., ‘Minorities at Haverford’, in Kannerstein, Spirit and the Intellect, pp. 109–16. ⮭

- Horowitz, H. L., The Power and Passion of M. Carey Thomas, New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1994, p. 342. ⮭

- See Goldstein, E. L., The Price of Whiteness: Jews, Race, and American Identity, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2006, chaps 1, 2, 4. ⮭

- Unknown to Mack, 5 March 1931. Morley, F., For the Record, South Bend, IN: Regnery/Gateway, 1979, p. 405. ⮭

- Sharpless, Story, pp. 228–29. ⮭

- Sharpless, Story, p. 25. ⮭

- Sharpless, Story, pp. 128, 144–45, 174. ⮭

- Baltzell, E. D., Philadelphia Gentlemen: The Making of a National Upper Class, Glencoe, IL: Free Press, 1958, p. 225; Sharpless, ‘President’s Report’ (November 1922), p. 10. ⮭

- Data for 1892–1893: Sharpless to Wing, 8 November 1897; for 1888–1889: ‘Report of Educational Progress in Philadelphia Society of Friends’, Sharpless Presidential Papers, Letterbook, 1897–1902, pp. 210–11; for 1921–1941: ‘President’s Report’, HCB 21–39; for 1942–1943: ‘President’s Report’, 1941–1942, Haverford College Reports, Box 10; for 1943–1945: ‘President’s Report’, HCB 42–43. ⮭

- Sharpless, Story, pp. 98–99. ⮭

- Sharpless, Story, pp. 105–06. ⮭

- Baltzell, Philadelphia Gentlemen, pp. 265–67, 320. ⮭

- Benjamin, Philadelphia Quakers, pp. 19, 217. ⮭

- Morley, For the Record, pp. 364–65. ⮭