When George Fox preached in the open air on Firbank Fell in June 1652, some of the older members of his audience thought it odd that he was preaching on the hillside rather than in the nearby church. But, as he put it, ‘I was made to open to the people that the steeplehouse & that ground on which it stood was no more holier than that mountain’.1 In this, he was articulating a fundamental tenet of Quakerism, that we may encounter God’s spirit anywhere and at any time, so that no place or time is holier than another. The distinction between the sacred and the secular is false, as all places and times are potentially sacramental.2 Notwithstanding Fox’s preaching, Quakers, like many other religious groups, have endowed certain places with an aura of holiness and gone out of their way to visit them and to seek inspiration there.

In this, Quakers are expressing an idea that seems to be universal, namely that particular places hold memory and meaning for individuals and groups, making them stand out from the generality of the landscape around them. That meaning is usually generated by their association with past events, so that they become ‘storied ground’, to use the term coined by Paul Readman in his work on the role of place in constructing and fostering English national identity in the nineteenth century. He argues that the stories attached to such places create a ‘felt presence of the past’, giving them a ‘potent associational value’ because of their historical links.3

Since the beginning, Quakers have been strongly aware of their separate and distinct identity as a religious group. It was an identity that extended beyond their particular doctrines and form of worship and was reinforced for much of their history by the traditional peculiarities of lifestyle and culture that set them apart from their neighbours—‘plainness’ in speech and dress; uncompromising directness in the cause of Truth and integrity. Quaker origin stories helped to foster group identity from an early date: witness the publication of George Fox’s journal in 1694 and the collection by London Yearly Meeting in the early eighteenth century of accounts of the early days of individual meetings across Britain.4 Events and individuals were often linked to particular places, the name of Swarthmoor Hall being firmly associated with George Fox and Margaret Fell; Jordans in Buckinghamshire with William Penn and Isaac Penington, for example. By the later eighteenth century, the association between story and place drew Friends travelling in the ministry to visit those places because of their historical significance. These were early expressions of what may be termed Quaker pilgrimage, a phenomenon that mushroomed across the twentieth century, especially in the region now known as ‘the 1652 Country’ in north-west England, where a succession of sites has gelled into an itinerary of special places associated with Fox’s preaching journey in 1652.5

My aim in this lecture is to explore the concept of ‘storied ground’ in relation to the shaping of Quaker history and identity by focussing first on two windswept hillsides in Cumbria where there are rocks bearing the name ‘George Fox’s Pulpit’, harking back to the early days of Quakerism in the region. The better-known today is that on Firbank Fell, on the side of the Lune valley near Sedbergh; the other lies around 40 miles further north, on Pardshaw Crag, near Cockermouth, on the north-western edge of the Lake District.6

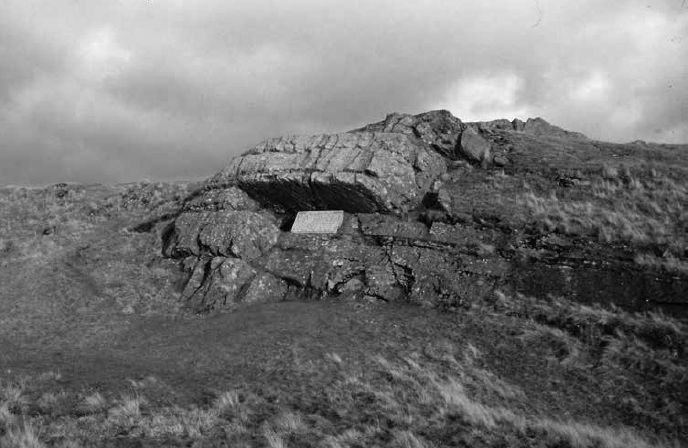

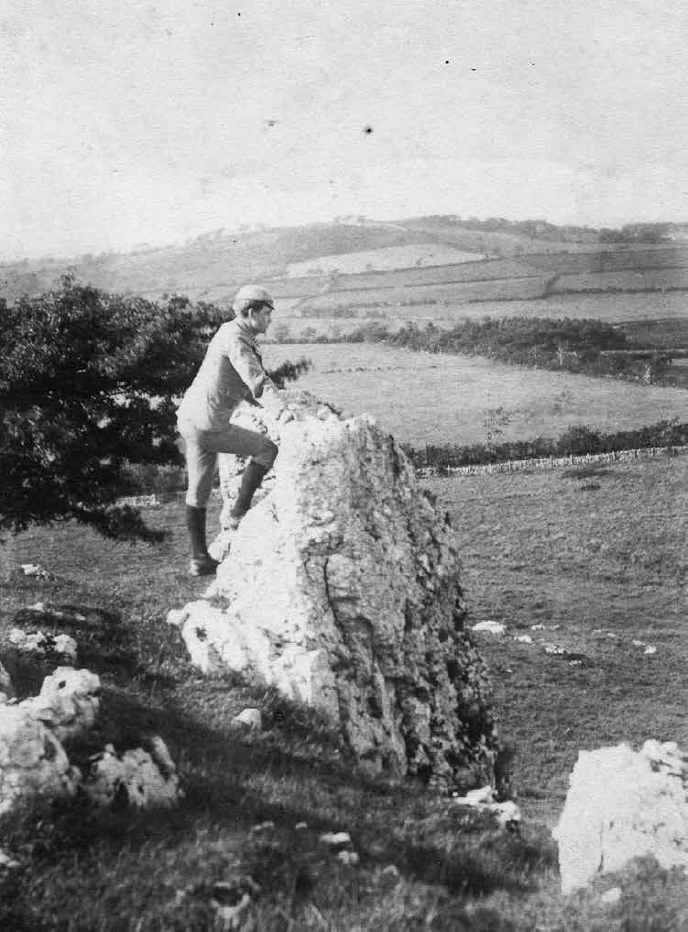

A comparison of the two allows us to begin to tease out some strands in the evolution of Quaker ‘storied’ places. The contrasts between the two sites are striking. Fox’s Pulpit on Firbank Fell (Fig. 1) is named and marked as a ‘Tourist Feature’ on the modern Ordnance Survey Outdoor Leisure map and is at a location that played a pivotal role in early Quaker history. Its fame, however, is fairly recent, being largely a product of the rekindling of interest in Quaker roots in the renewal of British Quakerism from around 1900—part of the modern ‘invention’ of heritage, in which Firbank became an established part of pilgrimages to the 1652 Country. Pardshaw Crag (Fig. 2), by contrast, though physically more convincing as a pulpit, is less often visited today and is not marked on the modern map. However, it was almost certainly the better-known ‘pulpit’ for much of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. In exploring the changing fortunes of the two sites and their relationship to the evolution of conceptions about the Quaker past, this lecture falls into two parts. The first charts what is known about the two pulpit sites; the second broadens the focus to trace the evolution of Quaker pilgrimage.

Firbank Fell

Fox’s Pulpit on Firbank Fell is a rock outcrop on the former common, beside a small walled enclosure in which the chapel of ease for Firbank township stood from the seventeenth century until it was destroyed during a storm in 1838.7 The chapel is of central significance in the events of 1652, as it was there that Fox first encountered large numbers of the Separatists of southern Westmorland, north Lancashire and the north-west of Yorkshire, now known collectively as the Westmorland Seekers. Many Seekers, including several of their preachers, were convinced by Fox on Firbank Fell and added the weight of their missionary zeal to his, effecting a step change in the scale of the early Quaker movement.

Fox had reached the Sedbergh area at Whitsuntide 1652 and attended a gathering of the Separatists at Firbank chapel the following Sunday. After the Separatist leaders had preached in the chapel in the morning, he preached out on the hillside. In his own words:

I came and sat me down on top of a rock—for the word of the Lord came to me, I must go and set down upon the rock in the mountain even as Christ had done before. And in the afternoon the people gathered about me with several Separate teachers, where it was judged there was above a thousand people, and all these several Separate teachers were convinced of God’s everlasting truth that day; amongst whom I declared freely and largely God’s everlasting truth and word of life, about 3 hours.8

Memories of the event would have resonated among local Friends, passed down the generations by word of mouth. We catch a glimpse of this when John Griffith of Philadelphia travelled through the area during a religious visit in 1748 and recalled how James Wilson, an elderly local Friend, had regaled him with ‘pleasing accounts’ about George Fox and ‘the spreading of Truth in those parts’, which he had heard from ‘eye witnesses, who were themselves convinced at that time’.9 However, there is little evidence that travelling ministers went out of their way to visit Firbank chapel (which returned to being an Anglican place of worship from the 1660s) or the adjacent rocky hillside.

By the 1850s, however, the draw of places associated with Fox and the early Friends had begun to rekindle an interest in Firbank Fell. In 1852, at the start of the bicentenary of the events of 1652—though without any hint of being a commemoration of those events—The Friend (London) carried an article entitled ‘Mountains and Mountain Devotion: Firbank Fell’, signed ‘W.T.’, who is probably to be identified with the Quaker schoolmaster, William Thistlethwaite (1813–70) of Wilmslow.10 Ultimately a reflection on the spiritual significance of mountains, it included an account of the author’s visit to the Sedbergh area in the autumn of 1851, Fox’s journal in hand, during which he made ‘a pilgrimage’ to the site of the chapel on Firbank Fell. ‘W.T.’ was keenly aware of spirit of place and of ‘brotherhood’ with those who had been there before: ‘we delight to wander over the places they wandered, to visit the rocks, the hills and the brooks … to interrogate their silent oracles and to enjoy through them a more earnest and enduring sympathy’, he wrote. The permanence of the rock on Firbank would ‘long point the weary pilgrim to the interesting spot’.11 W.T.’s account of his visit to Firbank Fell in the autumn of 1851 implies that ‘pilgrimage’ (the term he used) to the site was already becoming established, aided no doubt by the arrival of the railway with a station at Lowgill, two miles north of Firbank Fell, in 1846.12

When organised pilgrimages brought groups to the early Quaker sites from the early twentieth century, Fox’s Pulpit on Firbank Fell became a popular destination. Its importance in Quaker history was recognised by 1915, when a plaque was placed on the rock on the occasion of an open-air meeting for worship on the fell, held as part of a General Meeting of Cumberland and Westmorland Friends.13 It read:

Let Your Lives Speak.

Here or near this rock George Fox preached to above one thousand Seekers for three hours on Sunday 13th June 1652. Great power inspired his message, and the meeting proved of first importance in gathering the Society of Friends. From this fell many young men went forth through England, with the living Word in their hearts, enduring manifold hardships as ‘children of the light’ and winning multitudes to the Truth.14

The plaque ensured that Fox’s Pulpit became a place of inspiration for Friends and also a heritage site known well beyond the Quaker community.

Pardshaw Crag

In the summer of 1653, George Fox turned his missionary attention to the county of Cumberland, reinforced by preachers who had been convinced by him in north Lancashire and Westmorland the year before. The mission to Cumberland laid the seeds of several large Quaker groups, including those in the Cockermouth area. Soon after Fox’s initial visit to Cockermouth, John Audland, Edward Burrough and Thomas Holme from Westmorland held further meetings, one of those convinced by them being Peter Head of Pardshaw, whose house became the first settled meeting place in the county. So many came to the meetings ‘that the houses could not contain them, but they met without doors, for many years, on a place called Pardshaw Cragg, & abundance of people crooded to the meets’.15 By 1656 the MP for Cumberland could complain that Quakers met ‘in multitudes and upon moors’, referring to the meetings on Pardshaw Crag and on other commons in the vicinity of Cockermouth and near Carlisle.16 A hostile commentator later noted a practical advantage of meeting on the ‘high-crags or clinty rocks’ at Pardshaw: Friends could, he said, ‘readily espye any who came to disturb their conventicles; and so they were wont to disperse before they were caught’.17

According to his journal, Fox himself visited Pardshaw Crag twice, in 1657, when he attended a meeting of ‘several hundreds of people’ and convinced John Wilkinson, the minister of the local parish church, and in 1663, when he held a ‘large General Meeting’ on the crag during a visit to Cumberland.18 Both were visits to established Quaker groups, not seminal moments in his ministry as his visit to Firbank had been in 1652.

Pardshaw Crag remained a place of Quaker worship for many years after Fox’s initial mission. Friends continued to meet there in the open, during the summer months at least, until they built a meeting house close by in 1672, forerunner of the existing meeting house, built in 1729.19 Pardshaw Meeting was described as ‘the largest country meeting in England’ by the mid eighteenth century,20 the seat of a monthly meeting and a place regularly visited by travelling ministers from both sides of the Atlantic. In contrast to Firbank Fell, Pardshaw Crag, rising behind the plot containing the meeting house, school and burial ground, was close to a venue where Friends regularly gathered and continued to be pointed out for its associations with the early days of Quakerism. Thomas Scattergood of Philadelphia, passing through Cumberland during his travels in England in 1797, noted catching sight of ‘a hill called Pardsay Cragg … where Friends in the beginning held their meetings in the open air’.21 Likewise, when John Barclay, a minister from the south of England, made his way to Pardshaw in 1826, local Friends ‘pointed out the rock, where [Fox] preached among the mountains’.22

The rock on the limestone scar became known locally as ‘the preacher’s clint’ (‘clint’ being the dialect term for a rocky cliff).23 Samuel Capper, a minister from Wiltshire, visiting Pardshaw Meeting in 1850, described the pulpit thus: ‘In the midst of one of the uppermost [terraces of rock] are two points of rock, about three feet high, which standing in an angular form, make a natural pulpit, called since G. F.’s day, “the Preacher’s Clint”’ (see Fig. 2).24 Although Capper linked it with Fox, it is striking that the local name for the rock did not, perhaps reflecting its use for Quaker worship for around 19 years, during which time it had presumably provided a platform for numerous ministers.

By the nineteenth century, however, Quaker writing on both sides of the Atlantic repeatedly associated Pardshaw Crag specifically with Fox. An element of exaggeration seems to have crept in, creating a story that linked Fox more closely to the crag than had been the case and making claims about the numbers who heard him there that do not appear to be substantiated by contemporary sources. William Jackson, visiting Cumberland in 1803, recorded that Pardshaw Crag was where Fox ‘used to hold meetings with the people’, going on to claim ‘great was the convincement. Thousands were gathered to the Truth’.25 To Anna Carroll from Reading, visiting in 1849, Pardshaw Crag was ‘where excellent George Fox so often held meetings in the open air and preached from the crag’.26 An essay by L. M. Hoag, published in Philadelphia in 1853, claimed that it was ‘where George Fox used to stand and preach to many thousand people at a time’.27 The claims of frequent visits by Fox and ‘thousands’ of converts appear to be a snowballing of historical associations without a basis in fact.

Pardshaw Crag gained renewed fame in 1857, when it was chosen as the site for a large temperance ‘picnic’, at which Neal Dow (1804–97), the American ‘father of Prohibition’, who was himself of Quaker stock, addressed a gathering said to be over 10,000 strong, many of them Friends.28 The common land on which the crag stood had been enclosed in 1815, so that Fox’s Pulpit was by then on private land, which was rented for the occasion. The gathering was presided over by Sir Wilfrid Lawson, the leading temperance campaigner in Cumberland, who alluded to the crag’s associations in his opening speech, telling his audience that the pulpit rock was ‘interesting from its having been used in former days for religious occasions’.29

The temperance gathering in 1857 seems to have rekindled interest in the pulpit site among Friends. Two months after Neal Dow’s visit, Richard H. Thomas, a minister from Baltimore, held a meeting for worship on the crag, attended by large numbers (estimated variously at around 500 or 1,000) ‘reclining on the grass or sitting on cushions’, including Friends from Carlisle, Cockermouth and Whitehaven, as well as people from the surrounding villages. One newspaper report wondered ‘whether from the days of George Fox … until Sunday last, anyone had ventured to occupy as an evangelist the natural rostrum on Pardshaw Crag’.30

Across the later nineteenth century Pardshaw Crag drew visitors, both Quakers (like the 44 members of Manchester First-Day School who climbed to the pulpit in 1865 after attending meeting for worship at Pardshaw) and others (including an outing from Cockermouth Workhouse in 1897 and members of Whitehaven Wesleyan Guild in 1903).31 It is striking that the crag was pointed out as ‘George Fox’s and Neal Dow’s pulpit’ during the workhouse outing, perhaps suggesting that its association with the temperance picnic was itself drawing visitors. The Friends Review (Philadelphia) had contained a poem about the crag in 1865, and the crag was again used as an open-air auditorium in July 1900, when a speaker, fund-raising under the auspices of local Quakers, addressed a meeting from Fox’s Pulpit to raise money for Indian famine relief.32

Pardshaw Meeting closed for weekly worship in 1922, but the complex of buildings gained new life as a hostel. Feelings of affection for and connection with the old meeting house and its adjacent crag have ensured that an awareness of Fox’s Pulpit has survived, even though it is known to far fewer Friends worldwide than the pulpit on Firbank Fell.

The Making of Quaker Pilgrimage

The history of the two pulpit sites should be seen in the context of the evolution of Quaker pilgrimage more broadly. As the evidence from both Firbank Fell and Pardshaw Crag demonstrates, the ‘felt presence of the past’ was drawing visitors to places associated with early Quakerism by the mid nineteenth century, who went out of their way to experience the conjunction of story and place. ‘How deeply interesting it was, to look back from this point to those early, highly favoured days’, wrote one visitor to Pardshaw Crag in the early 1860s.33 Indeed, Fox’s pulpits were not unique: the draw of ‘storied ground’ also brought Quaker visitors to other sites.

Foremost was Swarthmoor Hall, near Ulverston, widely viewed as George Fox’s home, and thus the place where the association with Fox was strongest. Though it was no longer in Quaker hands, it drew a regular flow of visitors by the middle decades of the nineteenth century, to the extent that the then owner claimed in 1842 that many pieces of its carved oak panelling had been stolen by those passing through. The hall’s historical associations (and those of the nearby meeting house, given to the local Friends by Fox himself) attracted American Friends in particular, the vicar of Ulverston, writing in 1885, calling it ‘the Mecca of the Philadelphian’.34 The 1860s also saw the name ‘Swarthmore’ being transferred to institutions founded by American Friends, honouring the memory of a place so closely linked to the early Quaker story. Swarthmore College in Pennsylvania was founded by Hicksite Friends in 1864; Swarthmore Farm, a model farm in Guilford County, North Carolina, established in 1867, was part of the programme to rebuild Quaker work in the South after the American Civil War.35

Places in London associated with George Fox were also drawing visitors by the nineteenth century. His grave in Bunhill Fields was said to be attracting ‘too much of the attention of visitors’ by around 1800, while the room at White Hart Court where he died was being shown ‘with affectionate interest’ by its non-Quaker occupier in the middle decades of the century.36

Jordans Meeting House and neighbouring villages near Beaconsfield (Bucks.) provided another cluster of sites linked to prominent early Friends, notably the Penn and Penington families. Those families had gone by the later eighteenth century and meetings at Jordans were discontinued in the 1790s, so that, as at Swarthmoor Hall, the buildings that drew visitors were part of Quaker history rather than active places of worship. Thomas Scattergood, travelling in the ministry in 1797, made a detour to ride out to look at Isaac Penington’s home, while in 1827 another minister, John Barclay, visited the ‘secret solitude’ of Jordans, to see the burial places of Penington, William Penn and Thomas Ellwood, and was shown some original letters of Penington’s.37

The graves at Jordans were the main draw, pointed out to visitors by the last surviving ‘aged Friends’ in the 1790s, but unmarked until stones were placed over them (possibly incorrectly) in 1862.38 It was said in the 1860s that the ‘attraction which ever leads us toward the spot where the departed great are known to rest’ had long drawn Friends to make ‘pilgrimages’ to Jordans. ‘None seem to cherish the spot more than the Americans’, who sought mementos, such as a cowslip root from Penn’s grave.39 An annual meeting for worship each June had been reinstated in 1851, this and the marking of the graves ensuring that Jordans remained recognised as a special place across the later nineteenth century.40 After the meeting was revived in 1910, and the adjacent stables were converted into a hostel, Jordans gained a further layer of associational memory as the training ground for the Friends Ambulance Unit during the First World War and was chosen as the venue for the first International Conference of Young Friends in 1920.41 By then, it could be referred to as ‘A Quaker Shrine’, a confirmation of its status as one of a handful of places of Quaker pilgrimage.42

It is striking that records of visits to the early Quaker sites seem to burgeon in the 1850s and 1860s, though it is not clear whether this represents a real growth of interest or is a product of the expanding number of Quaker periodicals in the middle decades of the century.43 Either way, interest in places associated with Quaker history should be seen in the context of the times, notably the growth of tourism, spurred by the coming of the railways and their accompanying guidebooks, which drew attention to sites worth visiting in towns and countryside along the lines.44 Firbank Fell, Pardshaw and Swarthmoor were all within walking distance of stations, for example,45 and the latter lay on the fringes of the Lake District, which drew increasing numbers of tourists in the Victorian age. Eliza Southall, a Birmingham Friend on a tour of the Lakes in 1851, may not have been the only Quaker visitor to include both Pardshaw Crag and Swarthmoor in her Lakeland itinerary.46 ‘Heritage tourism’ was part of the mix. The ‘London Friend’ who celebrated ‘George Fox’s Pulpit, Pardshaw Crag, Cumberland’ in verse in 1865, began their poem, ‘Who does not love to trace/The footsteps of the past[?]’.47

There was also a more specifically Quaker context. In America, doctrinal schisms fractured the unity of the trans-Atlantic Quaker culture from the 1820s. In Britain, the strict regulations governing marriage, grave markers and the outward peculiarities of speech and dress were relaxed by London Yearly Meeting in the decade 1850–60, representing a departure from the Quaker lifestyle that had held since the seventeenth century. At a time of profound change, perhaps the stability and continuity represented by places associated with early Quaker history increased their appeal to visitors.

The appetite for Quaker ‘sacred places’ before the twentieth century should not be overstressed, however. Traditional Quaker thought had been wary of placing Fox or other individuals on a pedestal, raising them to the status of saint or hero and, by extension, of turning the places associated with them into ‘holy’ ground. When William Savery visited Swarthmoor Hall in 1797, he was at pains to insist that going there made him feel ‘serious’ but ‘not superstitious’.48 The small stone marking Fox’s burial place in Bunhill Fields was removed and broken up somewhere around 1800 because it attracted too much attention from visiting Friends. In that instance, fear of superstition was heightened by the stone’s ‘no longer denoting anything real’, as it had been moved to a corner and hence no longer denoted the actual grave.49 Considerable heart-searching occurred as late as 1891, the bicentenary of Fox’s death, when Friends were urged to ‘remember’ rather than ‘celebrate’ the event and to avoid ‘lionising’ Fox. Even in 1924, as plans were drawn up to mark the tercentenary of his birth, concerns were expressed about ‘canonising’ or ‘hero worship’ of Fox, with an insistence that the focus should be on his message rather than the man himself.50

Despite such caution, the draw of Quaker storied ground gained pace after the awakening of interest in the historical roots of Quakerism in the early years of the twentieth century, in which explorations of George Fox and his message loomed large. In Britain, looking back to the Society’s roots formed an important element of the Quaker renaissance after the Manchester Conference in 1895. The following decades saw the foundation of the Friends Historical Society (1903); the publication of the manuscripts of Fox’s journals (1911, 1925) and of the early accounts of the origins of individual meetings (as First Publishers of Truth, 1907); and completion of the magisterial seven-volume ‘Rowntree’ history of Quakerism (between 1911 and 1921).51 Contemporaneously, there was an upsurge in historical interest among liberal American Friends. Rufus Jones argued that an historical perspective was needed to provide ‘a steadying force’, to enable American Friends to ‘make use of the accumulated experience of their people’.52 As Thomas Hamm glossed it, ‘Only historical study could clear away the distortions of quietism and the [evangelical] revival and recapture what was unique and vital in Quakerism’.53 Exploring their history would allow Friends to recapture the essence of pure, primitive Quakerism, much as Fox had sought to recapture the essence of pure Christianity in his day.

This was the context of the creation of ‘the 1652 Country’ as an idea and of visits to Firbank Fell and other storied places by Quaker groups in the early twentieth century. The first recorded group visits to sites in the 1652 Country appear to have been excursions during a summer school held at Kendal in August 1908 under the auspices of Woodbrooke Extension Committee, one of the residential gatherings that were a feature of British Quakerism in the Edwardian period. Kendal was chosen because of its location as an ideal centre for excursions—close to the Lake District but also ‘almost in the centre of the district where Quakerism first became a power in English life’.54 Those attending, which included some American Friends, made excursions to Swarthmoor and Firbank Fell, to Preston Patrick and to the early meeting houses at Brigflatts and Colthouse. The excursions ‘made marks on our lives, [because] the walk of those early Quaker men and women was so close to Christ’.55

Across the twentieth century, story and place gained prominence in Quaker conceptions of the past through the development of pilgrimages to the 1652 Country. Scruples about celebrating Fox and other early Friends seem to have waned after the First World War. A formal group gathering on Firbank Fell took place as part of the Fox Tercentenary General Meeting, based in Kendal in 1924, during which ‘a fleet of charabancs mounted the road to Sedbergh’ to visit Brigflatts Meeting House and Fox’s Pulpit.56 The 250th anniversary of the founding of Pennsylvania in 1932 saw a pilgrimage to Jordans and other places associated with William Penn in ‘the Chalfont country’ of Buckinghamshire, while, in 1936, 45 pilgrims from Bootham and the Mount schools in York, following in Fox’s footsteps from Pendle Hill to Swarthmoor, initiated the pilgrimages for sixth-formers at Quaker schools that were held annually from 1950.57 In 1936, The Friend (London) carried a series of articles, under the banner ‘A Quaker Pilgrimage’, describing ‘places of historic interest in areas where Friends may be holiday-making’. These cast the net wide, to include not only the 1652 Country, Jordans and Cumberland (including Pardshaw Crag),58 but also places associated with Quaker history in Devon and Cornwall, Yorkshire, Ireland and even Iceland.59 It is probably no accident that the first organised pilgrimages took place during that decade, at the height of the outdoor movement.

Group visits to the 1652 Country proliferated after the Second World War, initially mainly for young people, then increasingly for international groups of Friends.60 In a journey from Pendle Hill to Swarthmoor Hall structured around George Fox’s account of the events of 1652, the pilgrimage itinerary and the stories repeated at each stopping point created a narrative of Quaker origins firmly rooted in place, which was laid out with convincing clarity by Elfrida Vipont Foulds in her handbook to the 1652 Country, The Birthplace of Quakerism (several editions from 1952). The itinerary was moulded to fit twentieth-century circumstances, notably at Preston Patrick where Fox had had another memorable meeting with the Seekers in the chapel there in June 1652. As both the chapel and the meeting house close by were rebuilt in the nineteenth century, neither site offered the possibility of tangible experience of seventeenth-century heritage. Instead, the pilgrimage route included the nearby Preston Patrick Hall, a late medieval manor house that was in the ownership of a Quaker family by the mid twentieth century. A somewhat tenuous link to the events of 1652 was forged by focussing on the court room in the Hall, in which, by tradition, Thomas Camm from the adjacent farm of Camsgill, one of the Seekers convinced by Fox in 1652, was sued for non-payment of tithes.61 Although the pilgrimage route was never rigid and evolved over time (to include the Quaker Tapestry exhibition in Kendal from the 1990s, for example), it had the effect of formalising a ‘heritage trail’ and reinforcing the role of story at certain locations. It thus differentiated further the two pulpit sites that formed the starting point for this discussion. That on Firbank Fell—integral to the 1652 story—became better known; that on Pardshaw Crag—not part of that story—faded from view. The contrast illustrates the importance of an accepted narrative and, indeed, of the printed word, in transmitting the historical associations of storied ground. In the Quaker context, George Fox’s journal provided a near contemporary account that was then moulded three centuries later into a vivid and compelling story by the pen of Elfrida Foulds.

***

Standing back from the local detail, what conclusions may be drawn from this excursion into Quaker ‘holy’ places? A first step is to consider the meaning of Quaker pilgrimage.

When Ernest Warner described Jordans as ‘A Quaker shrine’ in 1921, he went out of his way to preface his booklet with a definition. A shrine was not sacred in itself, he said, but became holy through being a place of worship.62 The same idea was encapsulated in the extract from T. S. Eliot’s poem ‘Little Gidding’, read regularly at pilgrimages to the 1652 Country since 1953, in which pilgrims are instructed ‘to kneel / Where prayer has been valid’.63 As in other forms of pilgrimage, prayer, worship and an element of retreat and religious contemplation lie at the heart of Quaker pilgrimage.64 So does the experience of community with fellow pilgrims. In her exploration of the essence of Quaker pilgrimage, Kathleen Thomas stressed the ‘feeling of communitas among strangers … engendered by a journey to places where a common past is commemorated’, which in turn provides a ‘basis of inherited values’ for the group.65 Another aspect is the power of story. Beth Allen, who participated in numerous pilgrimages to the 1652 Country when General Secretary of Quaker Home Service, found that Quaker pilgrimages had the same feel as Anglican liturgy and rituals, ‘a dramatised story—a series of movements with commentary—which you go through with the expectation of deeper understanding and closeness to the originators and to the Spirit’.66 The mystical strand in modern liberal Quakerism has probably also played a part in drawing visitors to Firbank Fell and Pardshaw Crag, as pilgrims are attracted by outdoor worship and the association of spirituality with mountains (even if the pulpit sites are on green hills, rather than mountain peaks). Firbank Fell has been described as a place where the human spirit, exposed to the elements, encounters nature ‘in a natural harmony, stripped of pomp, pride and politics’.67

A second theme is the part special places have played in Quaker culture, especially the function shared stories fulfil in reinforcing a sense of group identity. The role of travelling ministers in fostering a uniform trans-Atlantic Quaker culture in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries has long been recognised. One aspect of that was the part ministers, especially those from America, played in keeping alive an awareness of stories and places linked to early Quaker history. By the middle decades of the nineteenth century, an increasing interest in Quaker roots is evident at a time of rapid change and improved ease of travel, anticipating by several decades the flowering and rediscovery of Quaker history after 1900. Modern international pilgrimages highlight common historical roots for Friends from the widely divergent traditions now found in Quakerism worldwide, as they share the experience of visiting places associated with the origins of their church. The transmission of story and Quaker identity to younger generations has also been important, forming a key part of the rationale behind pilgrimages to the 1652 Country among British Friends.

Yet there is a gentle irony in modern Friends bending their paths towards Firbank Fell to stand on Fox’s Pulpit. This is the very place where George Fox insisted that the so-called consecrated ground of the chapel was no more holy than the rocky outcrop beside it. If we believe that the breaking through of God’s spirit into human life is not limited to particular places and times, there is an inherent contradiction at the heart of the idea of seeking inspiration from Quaker ‘storied ground’. As place is central to pilgrimage, this presents a conundrum for a religious group that eschews any notion of ‘holy’ or ‘consecrated’ places. An unwillingness to accept that either church buildings or meeting houses were of themselves holy has been a constant in Quaker thinking, even if it was seldom articulated in formal advice.68 It is striking that the traditional testimony focussed not on places but on ‘times and seasons’, a refusal to recognise the liturgical calendar of mainstream Christianity and the (often earthily secular) customary practices associated with it. Before the growth of modern pilgrimage, traditional Quakerism presumably felt no need to spell out a testimony against endowing particular places with special spiritual significance. Modern pilgrimage thus challenges a traditional Quaker assumption, but one that was largely unwritten.

The attraction of storied ground in both Quaker and other contexts lies ultimately in the tangible, concrete nature of place. Visiting a place freighted with historical associations has a much more direct impact on the individual than the abstract conception of time that is involved when marking ‘times and seasons’. As Pamela Richardson has put it, ‘nothing can replace the intensity of the lived experience, of the sights, sounds and smells … the atmosphere and fellowship’.69 Moreover, experiencing place has the power to prompt the historical imagination, a point made so eloquently by G. M. Trevelyan:

The poetry of history lies in the quasi-miraculous fact that once, on this earth, once, on this familiar spot of ground, walked other men and women, as actual as we are today, thinking their own thoughts, swayed by their own passions, but now all gone, one generation vanishing after another, gone as utterly as we ourselves shall shortly be gone, like ghost at cockcrow.70

The power of place has long drawn pilgrims to stand where stirring events occurred in order to encounter the ‘felt presence of the past’. Despite the inherent contradiction with a belief that no place is holier than another, Quakers have not been immune to this. Whether we think of those nineteenth-century Friends taking cowslips from William Penn’s grave or pieces of ancient panelling from Swarthmoor Hall, or modern young Friends taking selfies on Firbank Fell, the impulse is the same: a desire to connect with and gain inspiration from the roots from which Quakerism sprang and to use the conjunction of place and story as an aid in doing so.

Notes

- George Fox’s Journal: Spence MS, f. 32r (image and transcript at https://www.lancaster.ac.uk/fass/projects/quakers/versions3.html, accessed 08/04/2022). ⮭

- See David L. Johns, ‘Worship and Sacraments’, pp. 260–73 in Stephen W. Angell and Pink Dandelion (eds), The Oxford Handbook of Quaker Studies, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013, pp. 266–67. ⮭

- Paul Readman, Storied Ground: landscape and the shaping of English national identity, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018. ⮭

- A Journal and Historical Account of the Life, Travels, Sufferings, Christian Experiences and Labour of Love in the Work of the Ministry of … George Fox, London, 1694; the accounts of individual meetings were published as The First Publishers of Truth, ed. Norman Penney, London: Headley Brothers, 1907. ⮭

- See Angus J. L. Winchester, ‘The discovery of the 1652 Country’, The Friends Quarterly 27(8) (1993), pp. 373–83; Pamela Richardson, ‘The 1652 Country’, in Avril Maddrell, Alan Terry and Tim Gale (eds), Sacred Mobilities: journeys of belief and belonging, London: Ashgate, 2016, pp. 115–28. ⮭

- Fox’s Pulpit, Firbank Fell is at SD 619 937; that on Pardshaw Crag at NY 104 256. ⮭

- The chapel replaced an earlier one, shared by the inhabitants of Firbank and Killington, which stood about a mile to the south, on the boundary between the two townships. According to Thomas Machell, the antiquary, writing in 1692, the chapel on the fell had been ‘lately built’ (Jane M. Ewbank (ed.), Antiquary on Horseback, Kendal: Cumberland & Westmorland Antiquarian & Archaeological Society, extra series XIX, 1963, p. 38) but evidence that Firbank had its own chapel by 1625 suggests that relocation to the fell had occurred well before Fox’s visit. I am grateful to Sarah Rose, Assistant Editor of the Victoria County History of Cumbria, for sight of the draft entry for Firbank in advance of publication. The date of the chapel’s collapse during a storm is reported in a letter to the Penrith Observer, 6 November 1928, p. 3. ⮭

- Spence MS, ff. 32–32v (image and transcript at https://www.lancaster.ac.uk/fass/projects/quakers/versions3.html, accessed 08/04/2022). The precise location is not clear from Fox’s account. In the earlier Short Journal, he stated merely that he ‘went upon the hill’, while the account prepared by local Friends in 1709 described the location as ‘hard by’ the chapel (Short Journal, p. 30 (image and transcript as above); Penney, First Publishers of Truth, p. 243). It is generally accepted that it was probably the prominent rocky outcrop nearest the site of the chapel, now known as ‘George Fox’s Pulpit’. ⮭

- Friends Library, V, p. 362. ⮭

- For whom, see Bernard Thistlethwaite, The Thistlethwaite Family: a study in genealogy, privately printed: London: Headley Brothers, 1910, pp. 23–24. William Thistlethwaite’s interest in Quaker history is confirmed by his Four Lectures on the Rise, Progress and Past Proceedings of the Society of Friends in Great Britain, London: A. W. Bennett, 1865. ⮭

- The Friend (London), 1st mo. 1852 (vol. X, no. 109), pp. 1–2; reprinted in Friends Review (Philadelphia), V (1852), pp. 526, 534–35. ⮭

- Michael E. Quick, Railway Passenger Stations in Great Britain: a chronology, Railway & Canal History Society, 5th edn, version 5.03, published online September 2021, p. 292. It is probably not a coincidence that ‘W.T.’ located the Firbank Fell area by reference to Lowgill Station. ⮭

- Journal of Friends Historical Society 12 (1915), p. 154. ⮭

- Journal of Friends Historical Society 12 (1915), p. 154. The plaque was replaced by an aluminium tablet in 1952, during the 1652 tercentenary celebrations, the wording of the final sentence being modernised and made more inclusive. It now reads: ‘Many men and women convinced of the Truth on this fell and in other parts of the northern counties went forth through the land and over the seas with the living Word of the Lord, enduring great hardships and winning multitudes to Christ.’ ⮭

- Penney, First Publishers of Truth, p. 37. ⮭

- J. T. Rutt, The Diary of Thomas Burton Esquire … from 1656 to 1659, Vol. I, London: H. Colburn, 1828, p. 170. Other open-air meetings were held at Settraw, near the village of Sunderland, on Broughton Moor and on Warwick Moor and Aglionby Moor near Carlisle: Penney, First Publishers of Truth, pp. 41, 43, 46, 68. ⮭

- Thomas Denton, A Perambulation of Cumberland 1687–8, ed. Angus J. L. Winchester with Mary Wane, Surtees Society, vol. 207, 2003, p. 116. ⮭

- The Journal of George Fox, ed. John L. Nickalls, London: London Yearly Meeting, 1975, pp. 314, 454. ⮭

- Penney, First Publishers of Truth, p. 41; David M. Butler, The Quaker Meeting Houses of Britain Volume I, London: Friends Historical Society, 1999, pp. 103–07. ⮭

- John Griffiths of Philadelphia, visiting in 1748: Friends Library, V, p. 362. ⮭

- Friends Library, VIII, p. 123. ⮭

- Friends Library, VI, p. 451. ⮭

- The name is recorded in The Wheat-Sheaf: or gleanings for the wayside and fireside (Philadelphia: W. P. Hazard, 1853), p. 52; Memoir of Samuel Capper (London: W. & F. G. Cash, 1855), p. 182; The British Friend, XV (1857), pp. 193, 234. ⮭

- Memoir of Samuel Capper, p. 182. ⮭

- The Friend (Philadelphia) 25 (1852), p. 302. ⮭

- The Friend (Philadelphia) 39 (1866), p. 255. ⮭

- The Wheat-Sheaf, p. 52. ⮭

- Reports of the event are in The British Friend 14(2) (1857), pp. 193–94; Kendal Mercury, 20 June 1857, p. 8. ⮭

- The British Friend 14(2) (1857), p. 194. ⮭

- The British Friend 15 (1857), pp. 234–35; Westmorland Gazette, 29 August 1857, p. 2. ⮭

- Mary Hodgson and Lydia Hunt, Excursion to Loweswater: a Lakeland visit, 1865, London: Macdonald & Co., 1987, p. 68; West Cumberland Times, 24 July 1897, p. 8; 8 July 1903, p. 2. ⮭

- Friends Review 18 (1865), p. 46; West Cumberland Times, 28 July 1900, p. 4. ⮭

- The Friend (Philadelphia) 37 (1863), p. 84. ⮭

- For Swarthmoor Hall as a ‘heritage’ site, see Angus J. L. Winchester, ‘Swarthmoor Hall, History and Tradition: the making of a Quaker Mecca’, Lancaster University Centre for North West Regional Studies Regional Bulletin, new series 10 (1996), pp. 24–36. ⮭

- For Swarthmore College, see Mary Ellen Chijioke, ‘What’s in a Name?’, Swarthmore College Bulletin (Feb. 1996), pp. 56–7; for Swarthmore Farm, see B. Russell Branson, ‘A period of change in North Carolina Quakerism’, Bulletin of Friends Historical Association 39 (1950), p. 77. ⮭

- William Beck and T. Frederick Ball, The London Friends’ Meetings: showing the rise of the Society of Friends in London …, London: F. Bowyer Kitto, 1869, pp. 155, 331n. ⮭

- Friends Library, VI, p. 453; VIII, p. 118. ⮭

- Buckinghamshire Heritage Portal, Monument Record 0433901000 (https://heritageportal.buckinghamshire.gov.uk/Monument/MBC11490, accessed 16/06/2022); Butler, Quaker Meeting Houses of Britain, I, pp. 25–26 gives the date of the headstones as 1850. ⮭

- Beck and Ball, London Friends’ Meetings, pp. 355, 358. ⮭

- W. H. Summers, Memories of Jordans and the Chalfonts, and the Early Friends in the Chiltern Hundreds, London: Headley Brothers, 1895, p. 266. For a description of these meetings, see Beck and Ball, London Friends’ Meetings, pp. 356–58. ⮭

- For which see Thomas C. Kennedy, British Quakerism 1860–1920: the transformation of a religious community, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001, pp. 414–20. ⮭

- Ernest Warner, Jordans: a Quaker shrine, past and present, privately printed, 1921, esp. pp. 13–16. ⮭

- Notably The Friend (Philadelphia) (1827–), The Friend (London) (1843–), The British Friend (1843–), The Friends Intelligencer (1845–), Friends Review (1848–) and Friends Quarterly Examiner (1867–): Joseph Smith, A Descriptive Catalogue of Friends Books Volume 2, London: J. Smith, 1867, pp. 393, 396–97. ⮭

- Readman, Storied Ground, p. 215, citing A. K. B. Evans and J. V. Gough, The Impact of the Railway on Society in Britain, Aldershot: Ashgate, 2003. ⮭

- Pardshaw was served by the station at Ullock, a couple of miles away, from 1866: Quick, Railway Passenger Stations, p. 450. ⮭

- Eliza Allen Southall, A Brief Memoir with Portions of the Diary, Letters and Other Remains of Eliza Southall, privately printed, 1855, p. 153. ⮭

- Friends Review 18 (Philadelphia, 1865), p. 46. ⮭

- Friends Library, I, p. 427. ⮭

- Beck and Ball, London Friends’ Meetings, p. 331, citing [Luke Howard], The Yorkshireman, a Religious and Literary Journal, Vol. IV, Pontefract, 1836, p. 115n. ⮭

- Malcolm Thomas, ‘George Fox Anniversaries: some precedents’, TS memorandum dated 23.viii.1987/4.i.1991. ⮭

- See Kennedy, British Quakerism 1860–1920, pp. 168–71, 197–210. ⮭

- Thomas D. Hamm, The Transformation of American Quakerism: orthodox Friends, 1800–1907, Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1992, pp. 154–55. ⮭

- Hamm, The Transformation of American Quakerism, p. 155. ⮭

- Friends Intelligencer 65 (1908), pp. 216–17. ⮭

- Ibid, p. 557. ⮭

- Newspaper report in Gloucester Journal, 9 August 1924, p. 4. ⮭

- The Friend (London) 94 (1936), pp. 653–55; Winchester, ‘Discovery of 1652 Country’, pp. 377–78. ⮭

- The Friend (London) 94 (1936), pp. 605–06, 652–55, 719–21, 797–98. ⮭

- The Friend (London) 94, pp. 626–28, 671–72, 698–700, 763–65, 777–78, 815–16. ⮭

- Winchester, ‘Discovery of 1652 Country’, pp. 377–82. ⮭

- Elfrida Vipont Foulds, The Birthplace of Quakerism: a handbook for the 1652 Country, 5th edn, London: Quaker Home Service, 1997, pp. 31–35. ⮭

- Warner, Jordans: a Quaker shrine, p. [5]. ⮭

- Winchester, ‘Discovery of 1652 Country’, p. 382. The quotation is from T. S. Eliot, Four Quartets, London: Faber & Faber, 1959, pp. 50–51. ⮭

- Angus Winchester, ‘The significance of pilgrimage’, The Friend (4 June 1993), pp. 714–15. ⮭

- Kathleen Thomas, ‘Post-modern pilgrimage: a Quaker ritual’, Journal of the Anthropological Society of Oxford 30(1) (1999), pp. 21–34 at p. 25. ⮭

- In an email to the author, 17 February 2022. ⮭

- Mark Richards, author of numerous walking guides, quoted in Richardson, ‘The 1652 Country’, p. 121. ⮭

- For example, no mention of it is made in either the 1833 or 1861 books of discipline of London Yearly Meeting. ⮭

- Richardson, ‘The 1652 Country’, p. 126. ⮭

- G. M. Trevelyan, An Autobiography and Other Essays, London: Longmans, 1949, p. 13. ⮭