From Phyllis Mack’s book Visionary Women: ecstatic prophecy in seventeenth-century England (1992) to Sarah Crabtree’s book Holy Nation: the transatlantic Quaker ministry in an age of revolution (2015), the subject of female ministers of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries is well-trodden territory. But much remains to uncover. My research and writing about gift giving and token exchange among early travelling Quaker women has revealed further information about Amsterdam-born Friend Gertrude Derix Niesen (unknown–1687) and English Friend Catherine Payton Phillips (1727–94). While both research findings relate to the education of Quaker children, the sources used to make these discoveries and the discoveries themselves are markedly different.

Studying The Testimony of That Dear and Faithful Man, John Matern (1680) has revealed that Derix Niesen, who later married Colchester Quaker Stephen Crisp, sent at least one of her sons to George Fox’s Waltham Abbey School. The possibility that Derix Niesen and her first husband, Adrian van Losevelt, sent at least one child to England for a thoroughly Quaker education further deepens our understanding of seventeenth-century Anglo-Dutch Quaker relations.

While the Matern testimony reveals additional information about a seventeenth-century minister, a group of samplers in the collection of the Quaker Tapestry Museum shines new light on an eighteenth-century one. The suite of four samplers was wrought by Hannah Payton (1716–61), sister of English minister Catherine Payton Phillips. Payton’s needlework unveils previously unknown information about Phillips’ upbringing, about which Phillips writes little in her book Memoirs of the Life of Catherine Phillips (1797).

Together, the Derix Niesen and Phillips discoveries unveil information about two early Quaker women not found in their own extensive writings. Though studying surviving documentation from Quaker women—their letters, journals, memoirs, and epistles—tells us much about these women and their religious endeavours, we can get a glimpse into the rich, minute details of their lives by studying these archival survivals alongside genealogical documents and extant material culture.

Uncovering Gertrude Derix Niesen’s Waltham Abbey Connection

Gertrude Derix Niesen (Geertruyd Dirricks Niessen in Dutch) was an early Amsterdam Quaker and travelling minister who authored numerous epistles in English and Dutch. She was a major figure in Dutch Quakerism—she housed William Penn during his visit in 1667, served as translator for Penn and Fox during their visits, befriended Quaker sympathiser Princess Elisabeth of the Palatinate, and hosted the Dutch monthly meetings in her home, ‘the Swarthmore Hall of Holland’, on the Keizersgracht.1 By the end of her life, she was deeply enmeshed in Quaker leadership in both England and the Netherlands.

Niesen’s first marriage, an unhappy one, was to a wealthy merchant named Adrian van Losevelt.2 According to Rosalind Thomas, the pair had three children: Corneli[u]s (perhaps born in 1662), William and Catherine.3 Gertrude brought her children with her to visit England at least once, in 1677.4 As this research note will reveal, William and perhaps Cornelius spent more of their childhood in England than previously thought.

In 1680, John (or Johann) Matern, one of the teachers at Waltham Abbey School, died of a fever.5 Matern, who had come from Silesia six years earlier with his family, had taught at Waltham Abbey from 1674 and seems to have been a universally admired teacher, colleague and friend.6 His death was commemorated by his fellow schoolteachers, Christopher Taylor and Alexander Paterson, his wife, Taylor’s wife, and his pupils, including Margaret Fell’s granddaughter Margaret ‘Nanny’ Rous(e) and Mary and Isaac Penington’s children William and Edward, in The Testimony of That Dear and Faithful Man, John Matern. Spanning pages 23 and 24, between testimonies by 11-year-old Ezekiel Wooley and ten-year-old Mary Taylor (presumably Christopher Taylor’s daughter), is a testimony by 12-year-old William Loosvelt, Gertrude’s younger son.

Loosvelt’s testimony is titled ‘This I have to Speak to the Praise of the Lord God and his Truth, as concerning our dear Teacher John Matern.’ In it, Loosvelt praises Matern’s fear of God and eschewing of evil while also lamenting what he sees as an increasing level of wickedness among the general population.7 While Loosvelt’s testimony largely aligns with that of the 11 other students who memorialised Matern in the book, he is the only one to have commented on a popular descent into iniquity.

Though we cannot absolutely confirm that the William Loosvelt who attended Waltham Abbey was the William van Losevelt whom Gertrude called son, it seems very likely that they are the same. Though Loosvelt’s birth, marriage, and death records have not yet been found, his birth year of 1667 or 1668 aligns with the approximate years of Gertrude’s marriage to van Losevelt, 1661–70.8 Cornelius’ absence in the Matern testimonies is likely due to his having finished his schooling, being 18 years old in 1680. If Gertrude sent her younger son to Waltham Abbey for a staunch Quaker education, chances are she sent her older son there, too.

William makes a rare archival appearance in the 1685 record of his mother’s marriage to Stephen Crisp. In the document, he follows his brother Cornelius, about whom many more historical documents survive. Though Cornelius’ birth and death records have also not been found, there is a surviving record of his marriage to Abigail Furly in Colchester on 18 May 1686, which William attended. There are also surviving records of the births and deaths of Cornelius’ many children, of whom we know Furly, Geertruid, Katherine, Cornelius and Anna.9 Only Anna lived past 19 years old and went on to marry. Neither William nor Cornelius attended her 11 July 1727 marriage to John Hails, suggesting that both brothers died before this date. Unlike William, whose occupation (if he lived to find one) remains unknown, Cornelius’ career is well documented. In 1693, the elder Cornelius, then a gentleman in London, filed a patent for ‘A New Engine for the Raising of Water, and For Craining and Lifting of Goods and Other Things of Weight, By An Artificial Flux and Reflux of Water.’10 We can even track where he lived and owned land in the city and beyond—in 1699, he was listed as being of Shadwell and having land in Southwark, but the listing of his children’s births and deaths in Colchester indicates he split his time between London and Essex.11 In comparison to his brother, William is almost entirely absent from the historical record. The lack of a marriage record for William and any records of children he fathered, as well as his absence from documentation after 1686, suggests he did not live to see 1690. What is likely, though, is that after his schooling he made England his permanent home.

William Loosvelt’s attendance at Waltham Abbey School is just one indication that the school’s role was much more international than has previously been asserted. When John Matern emigrated from Silesia to England to teach at the school, he brought with him his German brother-in-law, Ephraim Prach, who attended the school from 1674 to 1676.12 He then became an apprentice to a shoemaker, and his apprenticeship fees were paid in part by Derix Niesen, who was visiting England at the time.13 Matern’s widow, Rosina, married John Bringhurst, a Quaker printer who published at least 47 works for Friends.14 After Bringhurst was found to have printed a seditious text in 1685, he and Rosina fled to Amsterdam.15 Though it is not known the extent of their Quaker activities in the city, if they remained active Friends during their time in Amsterdam, they surely attended meetings at the Keizersgracht house once owned by Derix Niesen, which was the centre of Quakerism in Holland for more than 150 years.16 Before his escape to Holland, Bringhurst published The Epistle of Caution to Friends to take Heed of that Treacherous Spirit, written by Christopher Taylor, head of Waltham Abbey School and Matern’s boss. Clearly, both Derix Niesen’s connection to Waltham Abbey School and the role of Waltham Abbey School in the world of Quakerism outside Britain and its colonies both deserve further study.

Connecting Gertrude Derix Niesen to Waltham Abbey via William Loosvelt reveals a stronger connection that had previously been addressed between England, the birthplace and centre of Quakerism, and those who practised Quakerism in continental Europe. Waltham Abbey’s relationship to Europe has already been established in scholarship about Matern, but very little scholarship has before now examined the English–European relationships among its student body. Derix Niesen’s connection also adds further proof that though Waltham Abbey was presented as a boys’ school, women and girls were very much involved, as proven by Mary Penington’s boarding at the school and testimonies to Matern written by his wife Rosina, Christopher Taylor’s wife Frances, and students Mary Taylor and Margaret Rous(e).17

While the first half of this research note focuses on a major early school founded for Quaker boys (though not exclusive to them), the second half concerns itself with domestic education for Quaker girls. Both the Derix Niesen finding revealed above and the Catherine Phillips finding discussed below provide further information about the intersection of female Friends and early Quaker education, a subject never before explored in-depth in scholarship.

Understanding Catherine Phillips Through Her Sister’s Stitching

The Quaker Tapestry Museum in Kendal has in its collection three dated samplers stitched by Hannah Payton, worked in 1727, 1731 and 1751. There is a fourth, undated, sampler that was surely worked in between 1727 and 1731, given the level of stitching skill. It is very rare for multiple samplers by a single maker to survive. Hannah Payton (1716–61) the sister of famed travelling minister Catherine Payton Phillips, stitched these samplers between the ages of 11 and 35 in Dudley, Staffordshire. Given that very little needlework stitched by eighteenth-century travelling female ministers or their family members is known to survive, Payton’s four samplers provide a unique insight into the needlework education of children within ministerial families.18 Though travelling female Friends never wrote about their needlework, the expectation for women of the past to stitch often and the amount of extant embroidery worked by Quakers indicate that female ministers stitched during their journeys.19

Hannah Payton, the daughter of Henry and Elizabeth Fowler Payton, was from a family who had been Quaker for generations. Her father and aunt were travelling ministers, as was her youngest sister, Catherine, who travelled throughout the British Isles, the Netherlands and the American colonies.20 She married William Young of Leominster and had three children.21 Samplers made by their daughter, Ann Young (1748–unknown), are also held by the Quaker Tapestry Museum.

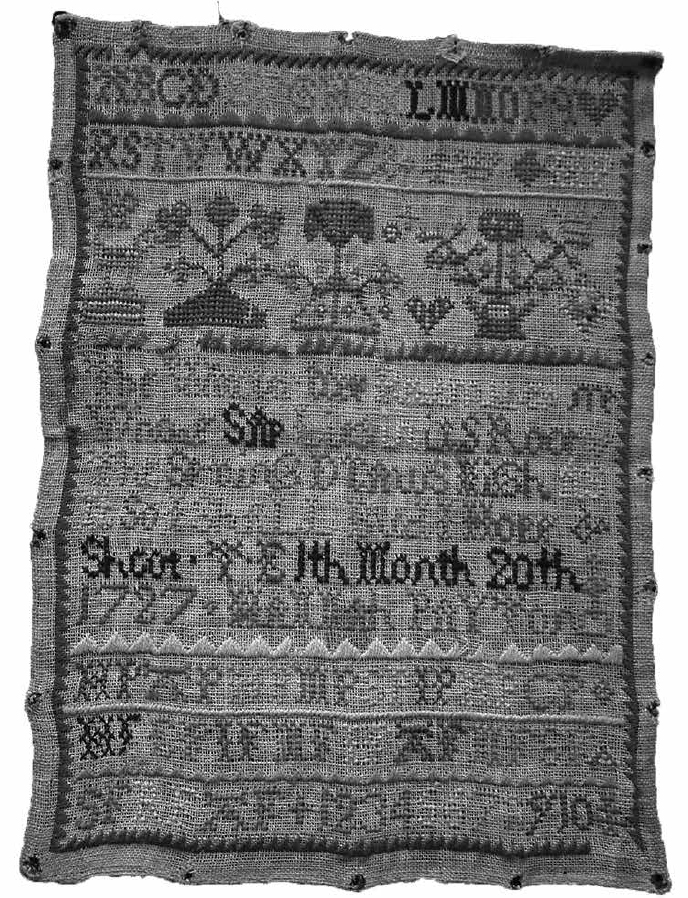

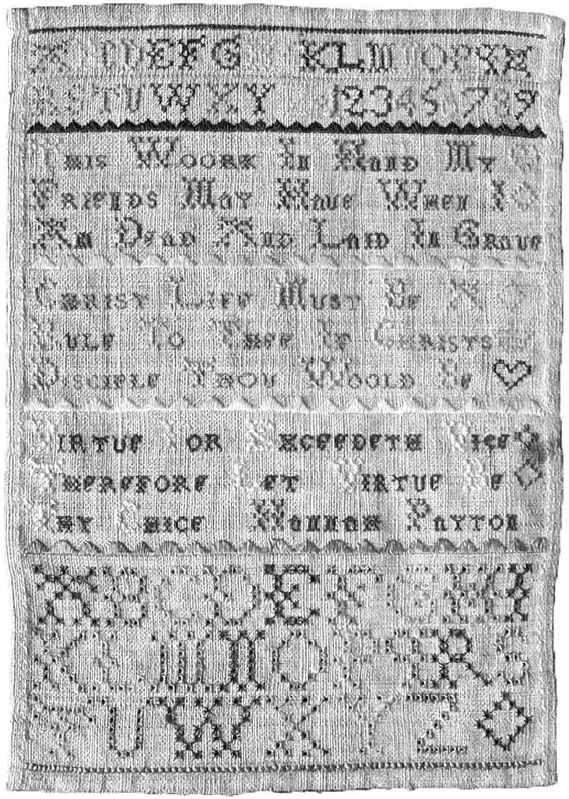

Payton’s samplers do not align with what is considered plain style to our twenty-first-century eyes, but further research has revealed that very little historical Quaker needlework did.22 Payton’s earliest sampler, dated 1727, combines a series of stylised motifs with an alphabet, a set of numerals, an inscription, a signature, and a lengthy set of family initials (Fig. 1). It includes a verse from The History of the Life of Thomas Ellwood and images including three flowers in vases, several hearts and a bird.23 The undated sampler, surely the second one stitched, is smaller than the first but it, too, features a mixture of alphabet, numerals, and inscription (Fig. 2). This sampler shows a natural progression of a stitcher’s skills, being significantly more text-heavy and worked in smaller stitches on a finer linen ground. For two out of the three verses, no source has been found thus far. The third, which reads, ‘CHRIST LIFe MUST Be A/RULe TO THee IF CHRISTS/DISCIPLe THOU WOOLD Be’, comes from Gerards Meditations (1638).24

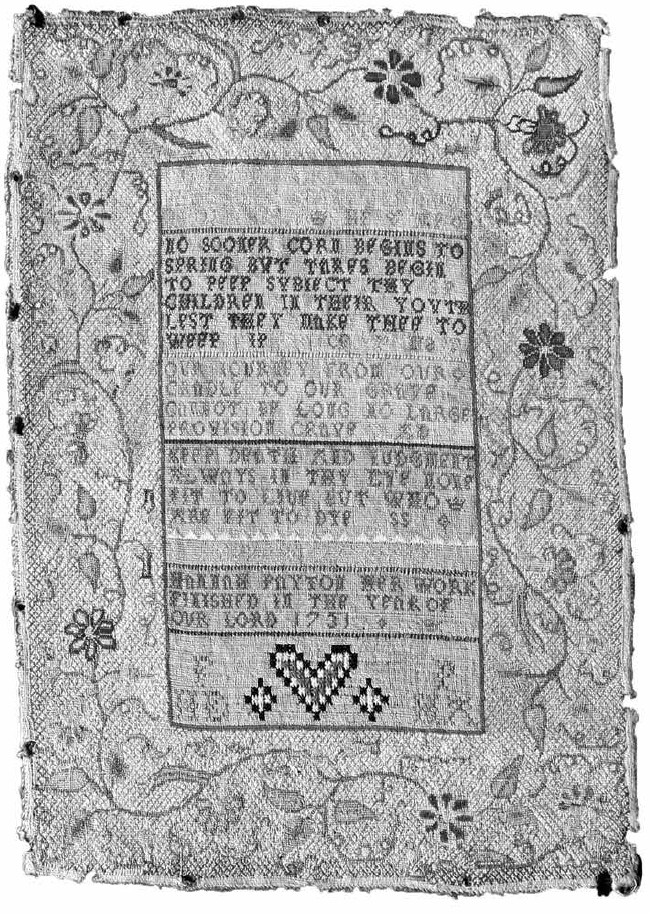

Payton’s third sampler, dated 1731, is the most decorative of the set (Fig. 3). Framing a series of inscriptions stitched with a background of yellow threads is a border of sinuous, flowering stems. Underneath the inscriptions Payton stitched, which are accompanied by sets of initials of family members or perhaps classmates, is a signature with her name and the year in which she completed her sampler.25 Below this are two trios of initials—’HEF’ for her maternal grandparents, Henry and Elizabeth Fowler, and ‘HAP’ for her parents, Henry and Anne Payton. The background of the floral border is worked in repeating diamond pattern of one long stitch flanked by two shorter stitches. Though not limited to just Quakers, this stitch style seems to have been employed by Quaker girls and women more than by anyone else, first appearing in Quaker needlework from the late seventeenth century.26 Payton’s sampler is far from plain, as indicated by its bright yellow threads, which retain their vibrancy on the sampler’s reverse. Payton’s final sampler, dated 1751, is the only one she worked as an adult and is stylistically divergent from its predecessors (Fig. 4). This wide sampler, with its two symmetrical floral and geometric designs worked in green threads, is reminiscent of the medallion samplers Quaker became known for towards the end of the eighteenth century.

Though Hannah’s sister wrote an autobiography, published after her death alongside some of her letters and epistles as Memoirs of the Life of Catherine Phillips, it does not reveal anything about the Payton daughters’ stitching education.27 Catherine writes that she was educated at home until she was 15, when she was sent to a boarding school in London.28 Even though she never mentions it, Catherine was likely taught needlework at home, as the vast majority of middling and upper-class girls in eighteenth-century England were taught to stitch well before teenagerhood.29 Perhaps she considered her domestic needlework education not important enough to write about, or perhaps she was taught at home while Hannah received her needlework education at school. Multiple samplers across just a few years suggest that either Hannah received a more formal stitching education or that Elizabeth Payton taught her daughters to stitch in an especially dedicated manner.

What does this set of samplers say about the upbringing of a significant Quaker minister born within a ministerial family? Though she never writes about it, Hannah’s samplers suggest that Catherine, too, received a thorough needlework education. The absence of it in her memoir points to a larger absence in Quaker women’s writing: though material evidence indicates that Quaker women of all walks of life stitched, they almost never wrote about their needlework in letters, diary entries or memoirs. Such an absence can perhaps be explained by the fact that stitching was quotidian and considered to be of little importance in comparison to the religious discourse Quaker women usually wrote about. Hannah Payton’s samplers demonstrate that, to understand more fully the lives of early Quaker women, we must look to their objects, not just their words. Both of these avenues of research, Gertrude Derix Niesen’s connection to Waltham Abbey School and Hannah Payton’s needlework suite, illustrate the value of looking in the margins, at a surname or a stitch. It is there that we can find not only more information about those early Quaker women we know by name and story, but also glimpses into the lives of women who did not leave behind their epistles or about whom no one gave a posthumous testimony. There is more to the early Quaker woman’s experience than diaries, journals, letters, and meeting minutes.

Notes

- Mabel Richmond Brailsford, Quaker Women, 1650–1690, London: Duckworth and Company, 1915, pp. 227, 229; Rosalind Thomas, Stephen Crisp and Gertrude (self-published, 2019), pp. 59–60; William I. Hull, ‘A History of Quakerism in Holland’, unpublished manuscript titled ‘Deriks, Geertruyd’, Swarthmore Friends Historical Library, RG 5/069, Box 24, p. 5. ⮭

- Thomas, Stephen Crisp and Gertrude, p. 51. Brailsford spells it ‘Loosefelt’. ⮭

- Thomas, Stephen Crisp and Gertrude, p. 53. Hull asserts that the pair only had two children, Cornelius and Gertrude, though he did not cite the source of this information in the unpublished ‘Deriks, Geertruyd’ manuscript. It is not possible to find the birth records of the Losevelt children without visiting Dutch archives, as the only digitised birth records are baptisms and the Losevelt children were surely not baptised. It is therefore not possible to determine if their daughter was Catherine or Gertrude. ⮭

- Thomas, Stephen Crisp and Gertrude, p. 63. ⮭

- ‘John Matern, Schoolmaster’, The Journal of the Friends’ Historical Society 10(3) (1913), p. 150. ⮭

- ‘John Matern, Schoolmaster’, p. 149. ⮭

- William Loosvelt, ‘This I have to Speak to the Praise of the Lord God and his Truth, as concerning our dear Teacher John Matern’, in The Testimony of That Dear and Faithful Man, John Matern, London: Benjamin Clark, 1680, pp. 23–24. ⮭

- Thomas, Stephen Crisp and Gertrude, pp. 51, 53. If Loosvelt was 12 when he wrote his testimony, he was born in 1667 or 1668. ⮭

- ‘England & Wales, Quaker Birth, Marriage, and Death Registers, 1578–1837’, Ancestry. com. ⮭

- English Patents of Inventions, Specifications, vols 301–500, London: H.M. Stationary Office, 1857, p. 3. ⮭

- ‘England & Wales, Quaker Birth, Marriage, and Death Registers, 1578–1837’, Ancestry. com. ⮭

- Dorothy Hubbard, ‘Early Quaker Education, c. 1650–1780’, unpublished master’s thesis, 1940, pp. 43–44; Sally Jeffery, Dissenting Printers: the intractable men and women of a seventeenth-century Quaker press, London: Turnedup Press, 2020, p. 49. ⮭

- Jeffery, Dissenting Printers, pp. 49, 109. ⮭

- Russell S. Mortimer, ‘The First Century of Quaker Printers II’, The Journal of the Friends’ Historical Society 41(2) (1949), p. 75. ⮭

- Sally Jeffery, ‘John Bringhurst, Seditious Printer’, Spitalfields Life, 13 August 2020, https://spitalfieldslife.com/2020/08/13/john-bringhurst-seditious-printer/. ⮭

- Hull, ‘Deriks, Geertruyd’, p. 2. ⮭

- Marie H. Loughlin, ‘Penington [née Proude, Mary [other married name Mary Springett, Lady Springett]’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, 23 September 2004, https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/45819; Taylor, The Testimony of That Dear and Faithful Man, pp. 25, 30. ⮭

- A select number of pieces by Rebecca Jones survive, but her childhood stitching dates to before her conversion to Quakerism. She brought a number of stitched objects back to Philadelphia from her 1784–88 ministerial travels through the British Isles, but who worked the embroidered pieces has not been determined. There are some surviving samplers by members of the intermarried Tuke and Grubb families. ⮭

- The connection between travelling ministers and needlework is the subject of this author’s final PhD thesis chapter. ⮭

- Rebecca Larson, Daughters of Light: Quaker women preaching and prophesying in the colonies and abroad, 1700–1775, New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1999, p. 51. ⮭

- ‘Monthly Meeting of Warwickshire North’, Ancestry.com; Catherine Payton Phillips, Memoirs of the Life of Catherine Phillips, to which are added some of her Epistles, London: James Phillips and Son, 1797, p. 199. ⮭

- Quaker women’s art (including needlework) and its opulence is the subject of this author’s PhD thesis. ⮭

- The verse reads, ‘The Winter tree Resembles me/Whose Sap Lies in its Root/The Spring Draws nigh As/It So I ShaLL Bud I Hope & Shoot.’ Thomas Ellwood, The History of the Life of Thomas Ellwood, London: J. Sowle, 1714, p. 89. ⮭

- Johann Gerhard, Gerards Meditations, trans. Ralph Winterton, Cambridge: Thomas Buck and Roger Daniel, 1638, p. 174. The first verse on the sampler reads, ‘THIS WOORK IN HAND MY/FRIeNDS MAY HAVe WHeN I/AM DeAD AND LAID IN GRAVe’ and the third, ‘VIRTUe FOR EXCeeDeTH VICe/THeReFORe LeT VIRTUe Be/THY CHICe.’ The last verse makes it especially clear how certain words, such as ‘far’ and ‘choice’ were pronounced in eighteenth-century Leominster. ⮭

- The first inscription on this sampler is not legible via photograph. The source of the second, ‘NO SOONeR CORN BeGINS TO/SPRING BUT TAReS BEGIN/TO PeeP SUBJeCT THY/CHILDReN IN THeIR YOUTH/LeST THeY MAKe Thee TO WeeP’, has not yet been found. The third is ‘OUR JOURNeY FROM OUR/CRADLe TO OUR GRAVe/CANNOT Be LONG NO LARGe/PROVISION CRAVe’ is from George Shelley’s Sentences and Maxims Divine, Moral, and Historical, London: Samuel Keble, 1712, p. 20. The final inscription, ‘KeeP DeATH AND JUDGMeNT/ALWAYS IN THY Eye NONe/FIT TO LIVe BUT WHO/ARe FIT TO Dye’, is from p. 62 of the same book. ⮭

- See the hussif worked by Hannah Downes or one of her daughters in the Victoria and Albert Museum and the hussif worked by Ann Marsh in the Chester County History Centre. ⮭

- Phillips, Memoirs of the Life of Catherine Phillips. ⮭

- Phillips, Memoirs of the Life of Catherine Phillips, p. 10. ⮭

- Amelia Peck, ‘American Needlework in the Eighteenth Century’, Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2003, https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/need/hd_need.htm. Though Peck discusses specifically American needlework in this essay, needlework education was very similar in England. ⮭